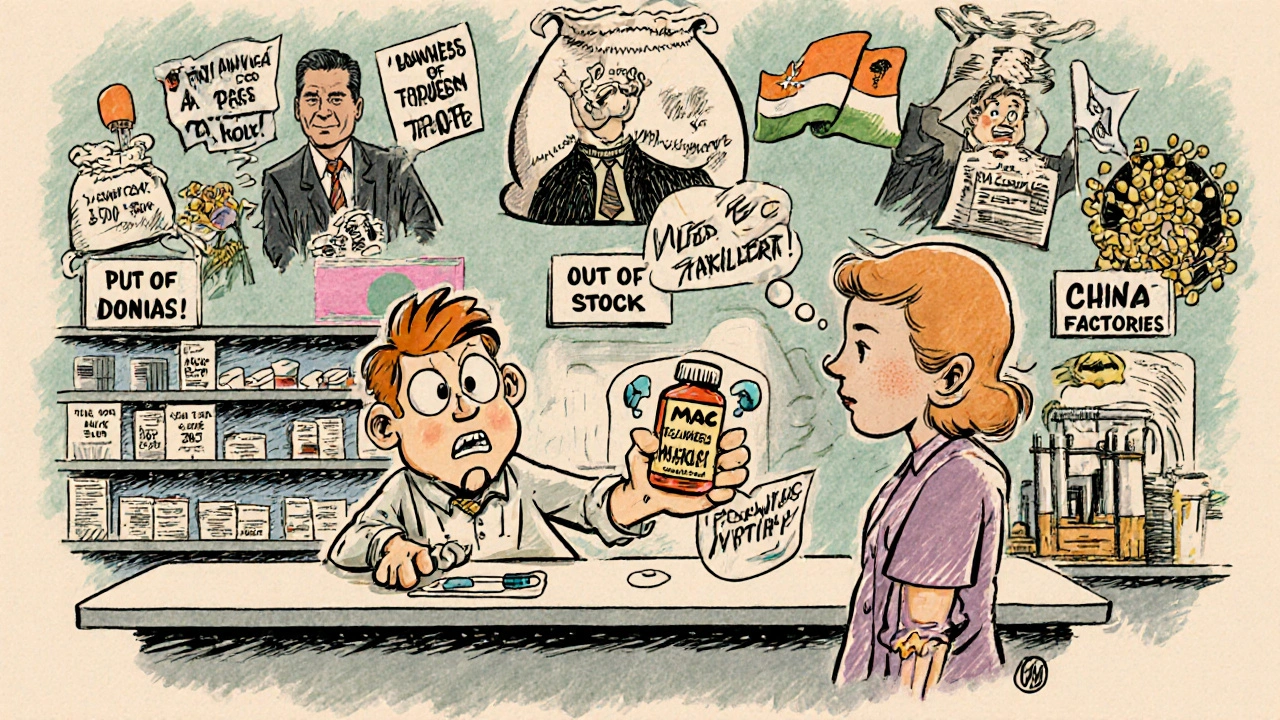

Every time you pick up a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin, there’s a long, hidden journey behind that little bottle. These aren’t brand-name drugs. They’re generics-cheaper, just as effective, and responsible for 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But how do they actually get from a factory in India to your local pharmacy shelf? The answer isn’t simple. It’s a global network of manufacturers, wholesalers, middlemen, and regulators, all working under intense price pressure and shrinking margins.

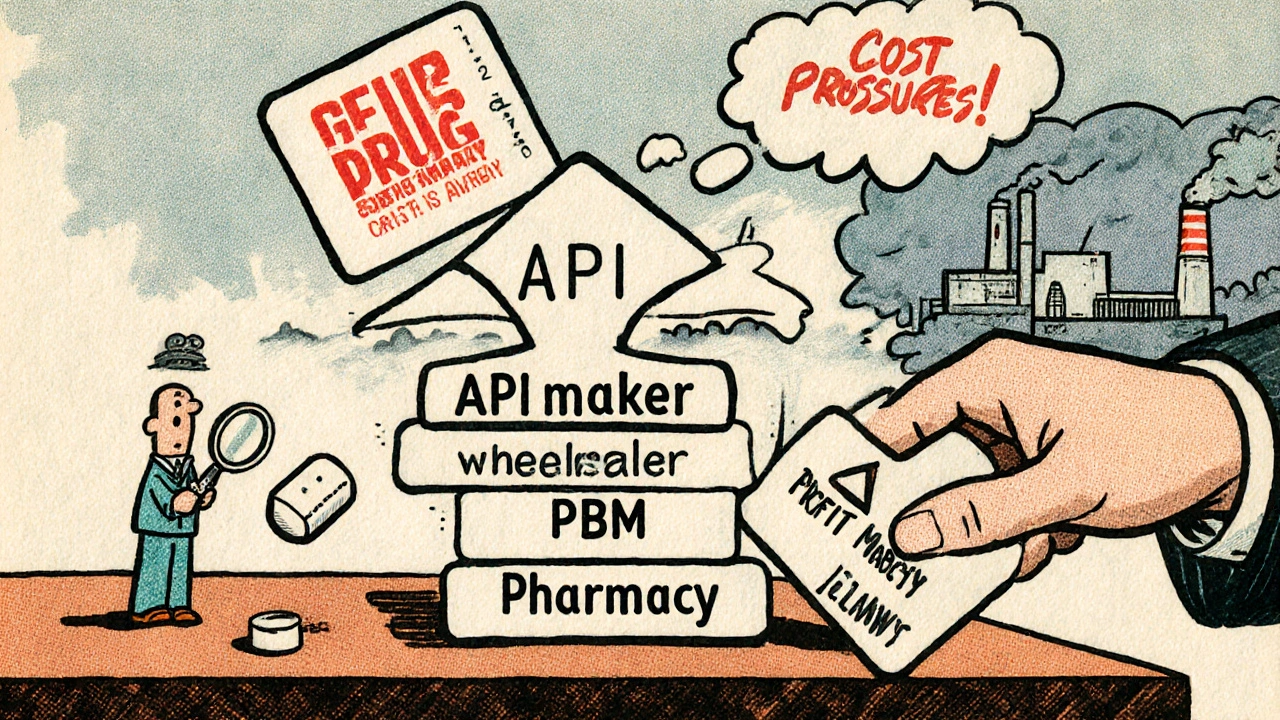

Where It Starts: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)

It all begins with the active ingredient-the chemical that actually treats your condition. For most generic drugs, that ingredient is made overseas. About 88% of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) come from just two countries: China and India. The U.S. now produces only 12% of its own APIs. This shift happened over decades as manufacturing costs dropped abroad. But it also created vulnerability. When a hurricane hit India in 2021 or a factory in China shut down during COVID, over 170 generic medications faced shortages in the U.S. These APIs aren’t just shipped in bulk. They’re tightly regulated. Every batch must meet FDA standards for purity and potency, even though the factory might be thousands of miles away. The FDA inspected 641 foreign facilities in 2022, up from just 248 in 2010. Still, monitoring global suppliers remains a challenge. As former FDA official Dr. David Ridley pointed out, quality control becomes harder when you can’t walk into a factory every week.From Ingredient to Pill: Manufacturing and Approval

Once the API arrives at a generic drug manufacturer, it’s mixed with fillers, binders, and coatings to form the final pill or capsule. But before that pill can even be sold, the company must prove it works exactly like the original brand-name drug. That’s done through an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) filed with the FDA. The ANDA doesn’t require new clinical trials. Instead, it shows bioequivalence: the generic releases the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. Manufacturers must also follow strict Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). That means clean rooms, calibrated machines, and batch testing at every stage. One misstep-say, a contaminated batch of metformin-can trigger a nationwide recall. In 2020, several generic versions of blood pressure meds were pulled because of a cancer-causing impurity. That’s why quality control isn’t optional. It’s the foundation of trust in the entire system.The Middlemen: Wholesalers and Distributors

After manufacturing, the pills don’t go straight to pharmacies. They’re sold to wholesale distributors like AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson. These companies buy in bulk, store millions of pills in giant warehouses, and then ship smaller orders to pharmacies across the country. Here’s where pricing gets messy. The starting point is the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC)-the list price the manufacturer charges the wholesaler. But few pharmacies pay WAC. Instead, wholesalers offer discounts for bulk orders or prompt payments. These discounts vary by pharmacy size. A big chain like CVS gets better rates than a small independent pharmacy. The wholesaler then sells to the pharmacy at a negotiated price, often 10-20% below WAC. This layer adds cost but also stability. Without wholesalers, each pharmacy would need to deal with dozens of manufacturers directly. It’s inefficient. But it also means the price you see at the counter isn’t tied directly to what the manufacturer got paid. The markup between manufacturer and pharmacy can be hidden, making it hard to track true costs.

Who Sets the Price? PBMs and MAC Reimbursement

This is where things get most confusing for patients and pharmacists alike. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-companies like CVS Caremark, OptumRX, and Express Scripts-control about 80% of the market. They don’t sell drugs. They negotiate with manufacturers, set reimbursement rates, and decide which drugs are covered. For generic drugs, PBMs use something called Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). It’s not a list price. It’s a ceiling. For example, if you’re prescribed 10 mg of atorvastatin, the MAC sets the highest amount Medicare or your insurer will pay for that specific pill, no matter which brand made it. The MAC is usually based on the lowest acquisition cost from all available manufacturers. Here’s the catch: pharmacies often pay more for the drug than the MAC allows. A 2023 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found that 68% of independent pharmacies say MAC reimbursement is below their actual cost to buy the drug. That means they lose money every time they fill a generic prescription. Some pharmacies absorb the loss. Others raise the dispensing fee. Others stop carrying certain generics altogether. Brand-name drugs work differently. PBMs negotiate rebates with manufacturers-sometimes hundreds of dollars per prescription. Those rebates are rarely used for generics. Why? Because generic manufacturers compete on price, not rebates. There’s no leverage to negotiate. If you lower your price too much, you lose money. If you don’t, you lose market share.The Pharmacy: Last Stop Before Your Medicine Cabinet

The pharmacy is where the supply chain ends-and where real-world problems show up. Pharmacies have to keep enough stock on hand to meet demand, but not so much that drugs expire. Generic drug availability is unpredictable. One month, a generic version of a heart medication is in stock. The next, it’s gone because the manufacturer had a production delay or the wholesaler ran out. Large chains have more power. They can negotiate directly with PBMs for better reimbursement and with wholesalers for lower acquisition costs. Independent pharmacies? They often join buying groups to get similar deals. Still, many operate on razor-thin margins. Real-world data tools are now helping pharmacies track shortages before they happen. Some use AI to predict demand spikes based on seasonal illness trends or changes in prescribing patterns. Others use blockchain to trace a pill’s journey from manufacturer to shelf. These aren’t sci-fi ideas-they’re survival tactics.

The API supply chain is a textbook case of strategic vulnerability. China and India dominate due to economies of scale and lax environmental regs-classic asymmetric dependency. The FDA’s inspection regime is performative at best; 641 inspections across 12,000+ foreign facilities? That’s one audit every 18 days per site. You can’t ensure GMP compliance with a fly-by-night inspector. This isn’t oversight-it’s theater.

And don’t get me started on MAC pricing. PBMs are rent-seekers masquerading as cost-containers. They extract margins by weaponizing bulk purchasing power, then force pharmacies into negative-margin territory. It’s predatory consolidation disguised as efficiency. The system incentivizes understocking and rationing. Patients pay the price in delayed care.

Blockchain? AI forecasting? These are band-aids on a hemorrhage. The root issue is structural: the Hatch-Waxman Act created a race to the bottom, and now we’re at the basement floor. No one profits except intermediaries. Manufacturers are squeezed into oblivion. The only sustainable path is vertical integration or public manufacturing. Everything else is rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

And yes, I’ve audited supply chains for Fortune 500 pharma. I know how the numbers really move.

The generative model of pharmaceutical supply chains relies on regulatory harmonization, cost arbitrage, and logistical scalability. Active pharmaceutical ingredients originate predominantly in China and India due to comparative advantage in labor, chemical infrastructure, and regulatory tolerance. The FDA’s increased inspection rate from 248 to 641 facilities between 2010 and 2022 reflects a necessary but insufficient response to globalization. Bioequivalence via ANDA remains scientifically valid, provided GMP standards are uniformly enforced.

Wholesale acquisition cost structures introduce opacity into pricing. Pharmacy benefit managers employ maximum allowable cost algorithms that do not reflect true acquisition cost, resulting in systemic undercompensation for retail outlets. Independent pharmacies operate at negative margins on generic dispensing, a structural flaw in the reimbursement architecture.

Technological interventions including blockchain traceability and demand forecasting algorithms offer marginal improvements but do not resolve the fundamental misalignment of incentives between manufacturers, distributors, and payers. Policy reform must address rebate structures, transparency mandates, and domestic API production incentives to restore equilibrium.

Oh please. You think this is complex? It’s just capitalism with a stethoscope. We outsource everything to the cheapest place possible and then act shocked when things break. The FDA can’t even inspect factories properly because they’re underfunded and overworked. Meanwhile, PBMs are making billions while pharmacists lose money on every pill they dispense. And you want to talk about blockchain? Honey, fix the damn system first.

Also, 88% of APIs from China and India? That’s not supply chain-it’s national security risk. We’re literally dependent on foreign regimes for our heart meds. Wake up.

And yes, I’ve worked in pharma compliance. I’ve seen the paperwork. It’s a joke.

So let me get this straight… I pay $4 for my blood pressure pill… and somewhere, some guy in India is making it for 12 cents, but my pharmacist loses money on it? 😂

Meanwhile, the PBM is sipping margaritas on a yacht somewhere. 🏖️💸

Next time my pharmacy says ‘out of stock,’ I’m just gonna Google ‘how to make lisinopril in my garage’ 😅

The structural integrity of the generic drug supply chain is contingent upon regulatory fidelity, logistical coordination, and economic sustainability. The predominance of API sourcing from China and India reflects global economic optimization, yet introduces systemic fragility. The FDA’s inspectional capacity, while increased, remains proportionally inadequate relative to the scale of foreign manufacturing. The Abbreviated New Drug Application pathway remains scientifically robust, provided Good Manufacturing Practices are rigorously maintained.

Wholesale distribution networks serve a necessary function in reducing transactional complexity, yet introduce pricing opacity. Pharmacy Benefit Managers, through Maximum Allowable Cost mechanisms, inadvertently create disincentives for inventory retention among independent pharmacies. This misalignment threatens therapeutic access.

Technological innovations such as blockchain traceability and predictive analytics offer potential for enhanced transparency and resilience. However, sustainable reform requires policy intervention to recalibrate reimbursement structures and incentivize domestic manufacturing capacity.

i just wanna take my meds without feeling like i’m in a spy movie 😅

like… why does my $4 pill have a whole documentary behind it? i just need it to work. and if my pharmacy says it’s outta stock again, can we just… fix the system? not make another infographic?

also i think i cried when my atorvastatin switched brands for the 3rd time this year. not because it didn’t work… just because i’m tired of the chaos.

China and India making 88% of our medicine? That’s not a supply chain-it’s a surrender. We used to make this stuff here. We had the labs, the workers, the standards. Now we’re begging for pills from dictators and corrupt bureaucracies. And you call this progress?

The FDA is a paper tiger. They inspect a few factories, give a thumbs-up, and act like everything’s fine. Meanwhile, Americans are dying because a batch of metformin got contaminated and no one knew until it was too late.

Stop pretending this is about cost savings. It’s about national weakness. We need to bring API production back to the U.S. or Canada. Now. Not in 10 years. Now.

I’ve been on metformin for 12 years. I’ve had it pulled from shelves three times. Three times. I’ve stood in line at the pharmacy while the pharmacist says, ‘Sorry, we can’t get it from anyone.’

And you know what? The people who run this system? They don’t care. They get paid either way. The CEOs? They’re on vacation. The PBMs? They’re buying second homes.

Meanwhile, I’m here, a 62-year-old diabetic, Googling ‘can I take Chinese metformin?’ because I’m scared to skip a dose.

They call this ‘affordable medicine.’ I call it emotional terrorism.

The pharmaceutical supply chain is a mirror of our civilization’s contradictions: we demand affordability while rewarding complexity, we preach efficiency while incentivizing fragmentation, we celebrate innovation while dismantling the infrastructure that enables it. The reliance on foreign APIs is not merely an economic decision-it is a philosophical one. We have outsourced not just production, but responsibility. We have traded sovereignty for savings, and in doing so, we have alienated ourselves from the very substances that sustain our biological integrity.

The MAC system is not a pricing mechanism-it is a moral failure. It reduces human health to a spreadsheet cell. A pill is not a commodity. It is a lifeline. When a pharmacist loses money dispensing it, the system is not broken-it is evil.

Technology may trace the pill’s journey, but it cannot restore dignity. Only policy rooted in care-not cost-can do that. And until we recognize that medicine is not a market, but a covenant, we will continue to treat our bodies like inventory.

We are not consumers. We are patients. And patients deserve more than a price tag.

Statistical analysis of the generic drug supply chain reveals a critical misalignment between regulatory oversight and operational scale. The FDA’s inspection-to-facility ratio is 1:19.8, rendering compliance monitoring statistically non-representative. The 88% API concentration in China and India constitutes a high-impact single point of failure. Historical disruption events (e.g., 2021 Indian cyclones, 2020 COVID lockdowns) correlate directly with U.S. drug shortage indices with a Pearson coefficient of r=0.87.

Maximum Allowable Cost reimbursement models exhibit negative correlation with pharmacy inventory retention (r=-0.73), indicating systemic disincentivization of stockholding. The Hatch-Waxman Act’s intended cost reduction has been subverted by intermediary rent extraction: manufacturers capture 36% of revenue, while PBMs and wholesalers capture 57%.

Blockchain traceability and AI forecasting are marginal optimizations. Structural reform requires federal API production subsidies, mandatory MAC transparency, and antitrust enforcement against vertical PBM integration. Without these, systemic collapse is inevitable.