What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

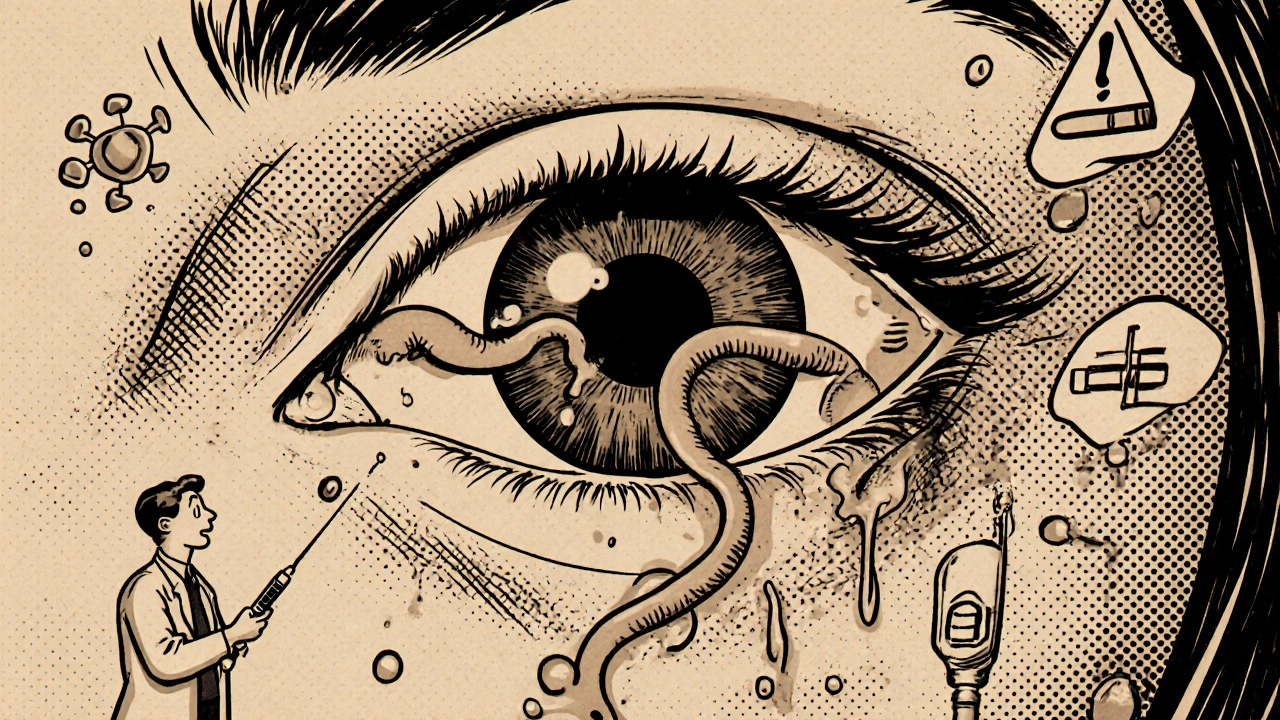

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out. This causes fluid to leak into the retina, leading to swelling - especially in the macula, the part of the eye that gives you sharp central vision. The result? Sudden, painless blurring or loss of vision in one eye. It’s not a slow, creeping problem. Most people notice it overnight or within hours.

There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which affects a smaller branch. BRVO is more common and often happens where a hard artery crosses over a vein, pinching it shut. CRVO tends to cause more severe vision loss.

It’s not rare. Around 16 million people worldwide have had RVO, and it’s one of the top causes of vision loss in people over 60. The good news? Treatment today can often save or even improve vision - if caught early.

Who’s Most at Risk?

RVO isn’t random. It’s tied to long-term health problems that affect blood vessels. The biggest risk factor? Age. Over 90% of CRVO cases happen in people over 55. Half of all cases occur in those over 65. But it can strike younger people too - about 5 to 10% of cases are under 45.

Here’s what increases your risk the most:

- High blood pressure: Present in up to 73% of older CRVO patients. Even if you think your BP is "controlled," unmanaged hypertension is the #1 driver of RVO.

- Diabetes: Affects about 10% of RVO patients over 50. It weakens blood vessels over time, making them more likely to clot or leak.

- High cholesterol: Total cholesterol above 6.5 mmol/L is found in 35% of RVO patients, no matter their age.

- Glaucoma: High pressure inside the eye increases risk, especially if the blockage happens near the optic nerve.

- Smoking: Around 25-30% of RVO patients smoke. It thickens blood and damages vessel walls.

- Obesity and inactivity: These contribute to hardened arteries - the main cause of vein compression.

For women under 45, birth control pills are a surprising link. They raise the risk of blood clots, which can trigger CRVO. Blood disorders like polycythemia vera or protein S deficiency also show up in younger patients.

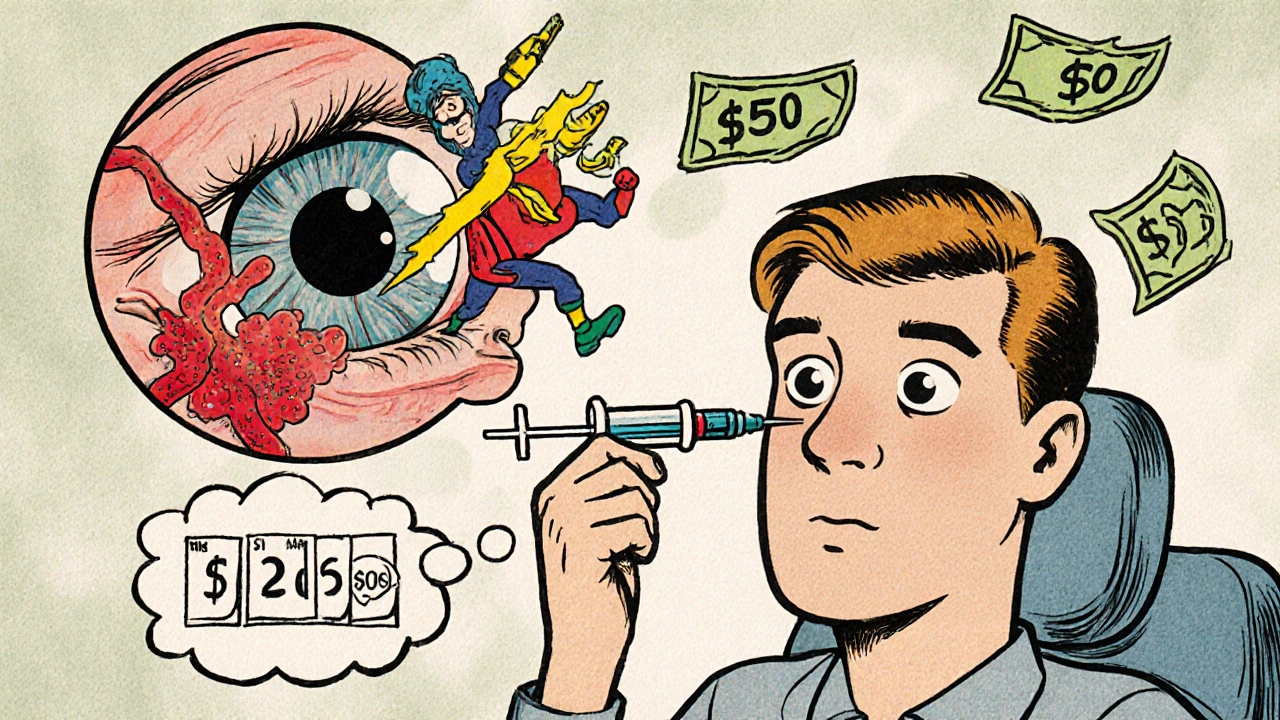

Why Injections Are the Standard Treatment

You can’t just "unclog" the vein. Once it’s blocked, the damage comes from the fluid leaking into the retina - called macular edema. That’s what blurs your vision. The goal of treatment isn’t to fix the blockage. It’s to stop the swelling.

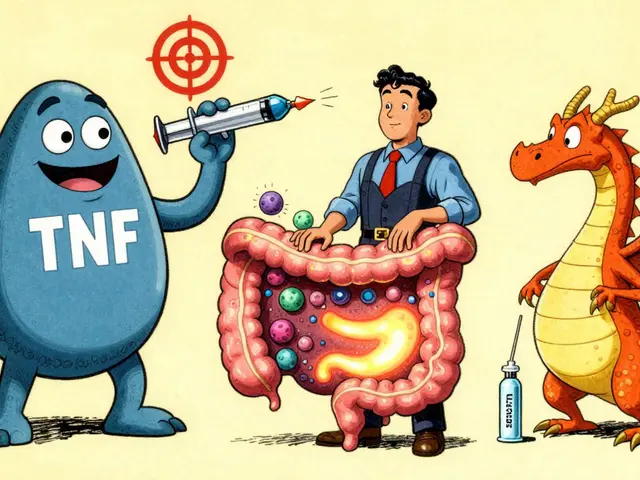

That’s where injections come in. These are tiny shots delivered directly into the eye, past the surface, to target the retina. Two main types are used:

- Anti-VEGF injections: These block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor that causes leaky blood vessels. Drugs like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) are used. Avastin is cheaper and used off-label, but all three work well.

- Corticosteroid implants: Like Ozurdex, a tiny biodegradable implant that slowly releases dexamethasone. It’s used when anti-VEGF doesn’t work well enough.

Studies show anti-VEGF injections can improve vision by 15-20 letters on an eye chart within 6 months. That’s often the difference between barely reading a clock and reading street signs again.

What to Expect During and After an Injection

The procedure takes about 5-7 minutes. Your eye is numbed with drops. The doctor cleans the area with antiseptic, holds your eyelid open with a speculum, and gives a quick injection. You might feel pressure, but not pain.

Afterward, you might notice:

- A red spot on the white of your eye (subconjunctival hemorrhage) - very common, harmless, fades in a week.

- Floaters - tiny specks drifting in your vision - usually gone in a day or two.

- Temporary blurry vision - lasts a few hours.

Serious problems like infection (endophthalmitis) are rare - about 1 in 5,000 injections. But if you get sudden pain, worsening vision, or light sensitivity after the shot, call your doctor immediately.

Most patients need monthly injections at first. After swelling goes down, the schedule shifts to "as needed," based on OCT scans that measure fluid thickness in the retina. If central subfield thickness stays below 250 microns, you might go 6-8 weeks between shots.

Real Patient Experiences

People’s stories vary widely.

One 62-year-old man got Lucentis injections every month after his CRVO. After four shots, his vision improved from 20/200 to 20/60 - enough to drive again. But he said the $150 copay each time hurt on a fixed income.

Another patient tried eight Avastin shots with little progress. Then he got the Ozurdex implant. In two months, his vision jumped 10 lines on the chart. He paid $2,500 out-of-pocket, but called it worth it.

Others struggle with the emotional toll. One woman on a patient forum said she missed appointments because the anxiety before each shot was worse than the pain. Another said she had 18 months of monthly injections and still kept going - even though her vision kept improving - because she didn’t want to lose what she’d gained.

Surveys show 78% of RVO patients see real vision gains with anti-VEGF therapy. But 63% say cost is a burden, and 41% feel exhausted by the treatment schedule.

Costs and Alternatives

Price matters. In the U.S., a single dose of Lucentis or Eylea costs about $2,000. Avastin, used off-label, is around $50. That’s why safety-net hospitals use Avastin in 60-70% of cases, while private practices use it less than 30%.

There are new options coming. The Port Delivery System (Susvimo), approved for macular degeneration, is now being tested for RVO. It’s a tiny refillable implant that releases medicine for months, cutting injections from monthly to quarterly.

Gene therapy is also in trials. RGX-314 aims to make the eye produce its own anti-VEGF protein, potentially eliminating the need for repeated shots.

For now, the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends anti-VEGF as first-line treatment. Steroids are saved for those who don’t respond - because they can cause cataracts in 60-70% of patients and raise eye pressure in 30%.

What’s Next for RVO Treatment?

The future is personalization. Doctors are starting to use OCT angiography - a detailed scan of retinal blood flow - to predict who will respond best to which drug. Some patients with very low baseline vision do better with steroids. Others with milder vision loss respond faster to anti-VEGF.

New studies show "treat-and-extend" protocols - where you start monthly and gradually space out shots based on response - work just as well as fixed monthly dosing, but with 30% fewer injections.

And research is looking at combo therapies: anti-VEGF plus a new drug called OPT-302, which blocks a different growth factor. Early results suggest it helps when standard treatment stalls.

The goal isn’t just to save vision. It’s to save people from the burden of endless shots. That’s the real breakthrough on the horizon.

Key Takeaways

- Retinal vein occlusion causes sudden, painless vision loss due to blocked blood flow in the retina.

- High blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, and smoking are the top risk factors - especially after age 55.

- Anti-VEGF injections (Lucentis, Eylea, Avastin) are the first-line treatment for swelling in the macula.

- Corticosteroid implants like Ozurdex are used when anti-VEGF doesn’t work well enough.

- Most patients need monthly injections at first, then fewer as swelling improves.

- Cost is a major barrier - Avastin is much cheaper than branded drugs and widely used in public health settings.

- Future treatments aim to reduce injection frequency with implants and gene therapy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can retinal vein occlusion be cured?

No, RVO can’t be fully cured - the blocked vein usually stays blocked. But treatment can stop the swelling and prevent further damage. Many patients regain significant vision, especially with early treatment. The goal is long-term vision stability, not a complete reversal.

How long do the injections last?

Anti-VEGF injections work for about 4-6 weeks. That’s why they’re given monthly at first. Steroid implants like Ozurdex last 3-6 months. New delivery systems in development could extend this to 6-12 months.

Are eye injections painful?

Most patients feel only pressure or a brief sting. The eye is numbed with drops, and the needle is very fine. The anxiety before the shot is usually worse than the procedure itself. The whole thing takes less than 10 minutes.

Can I drive after an injection?

Not right away. Your vision may be blurry for a few hours. Your pupils may also be dilated. It’s safest to have someone drive you home. Most people can drive again the next day.

What happens if I skip an injection?

Fluid can build up again, causing vision to worsen. Missing appointments can undo progress. Studies show patients who stick to their schedule keep better vision long-term. If you’re struggling with cost or anxiety, talk to your doctor - there are options to help.

Can RVO affect both eyes?

It usually affects just one eye at first. But if you’ve had RVO in one eye, your risk of it happening in the other eye is higher - about 10-15% over five years. Regular check-ups are essential.

13 Comments

Write a comment