Hemophilia is a rare inherited bleeding disorder caused by deficiency of clotting factors, most commonly factor VIII (Hemophilia A) or factor IX (Hemophilia B). It follows an X‑linked recessive pattern, meaning it predominantly affects males while females are carriers.

Early Records and the Birth of the "Royal Disease"

The term "royal disease" first appeared in the 19th‑century British press, pointing to the strikingly high concentration of hemophilia in Queen Victoria’s descendants. Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901 and is now recognized as the matriarch of the hemophilia lineage because several of her children and grandchildren inherited the condition. The most infamous case was Prince Leopold the youngest son of Victoria, who died at age 19 from a brain hemorrhage after a minor fall. His death sparked medical curiosity and laid the groundwork for systematic study.

Discovery of the Missing Clotting Factors

In the 1930s, researchers like Friedrich P. Baxter identified the blood‑borne protein missing in hemophiliacs began isolating the elusive factors. By 1944, Factor VIII was characterized as the essential coagulant whose absence defines Hemophilia A. A year later, Factor IX was linked to Hemophilia B, sometimes called Christmas disease after the first patient described.

Plasma‑Derived Therapies: The First Real Hope

The post‑World‑II era saw the first transfusion‑based treatments. Blood banks collected large volumes of donated plasma, which were then fractionated to concentrate factor VIII and IX. These "plasma‑derived" products reduced fatal bleeds but introduced new risks, most notably viral transmission. By the 1970s, hepatitis C and HIV outbreaks among hemophiliacs underscored the need for safer manufacturing.

Recombinant Clotting Factors: Clean and Consistent

The 1980s biotechnology boom delivered recombinant factor proteins produced in genetically engineered cell lines, free of human blood contaminants. Recombinant Factor VIII (rFVIII) entered clinical use in 1992, followed by recombinant Factor IX (rFIX) a few years later. Their introduction lowered infection rates dramatically and paved the way for personalized prophylaxis.

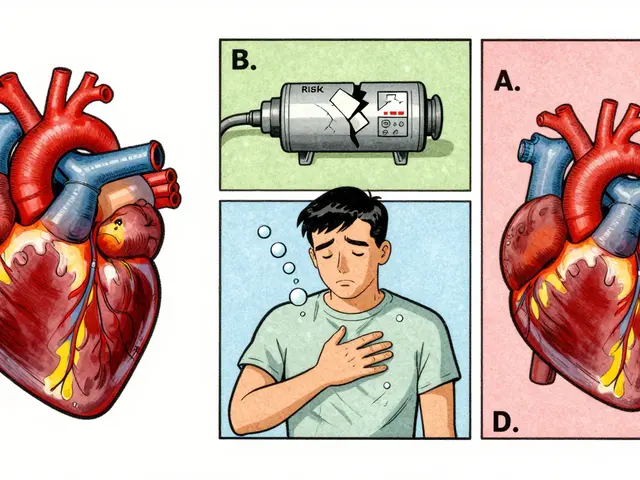

Inhibitor Development: A Major Clinical Challenge

Despite improved safety, up to 30% of severe hemophilia A patients develop neutralizing antibodies called inhibitors immune proteins that block the activity of infused clotting factors. Detecting inhibitors relies on the Bethesda assay a lab test that quantifies inhibitor strength in Bethesda Units (BU). Management often requires bypassing agents like activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) or newer non‑factor therapies.

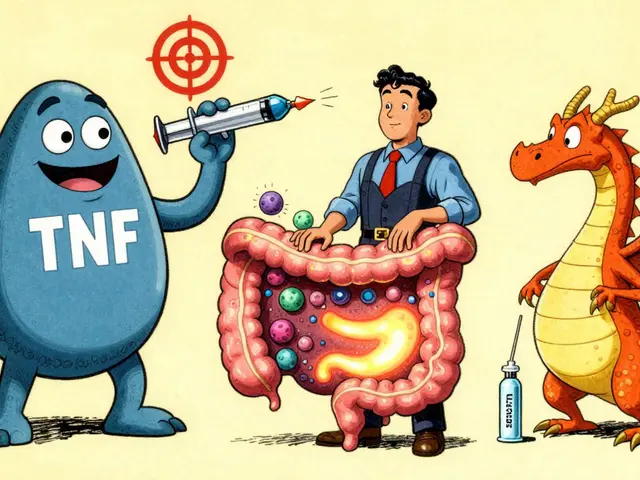

Gene Therapy: Toward a Functional Cure

In the 2010s, clinical trials using adeno‑associated virus (AAV) vectors to deliver functional copies of the F8 or F9 gene showed sustained factor expression after a single infusion. Gene therapy aims to convert severe hemophilia into a mild or even asymptomatic state by restoring endogenous factor production. Recent phase‑III data report mean Factor VIII levels of 30-50 IU/dL, sufficient to prevent spontaneous bleeds without regular infusions.

Global Advocacy and the Role of the World Federation

Patient advocacy shifted from isolated royal families to organized global movements. The World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) is an international charity that provides education, funding, and policy guidance to over 150 member organizations. Their "Global Survey" tracks treatment access, revealing that less than 15% of hemophilia patients in low‑income countries receive regular factor therapy.

Comparison of Major Hemophilia Subtypes and Related Disorders

| Disorder | Deficient Factor | Genetic Pattern | Prevalence (global) | Standard Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemophilia A | Factor VIII | X‑linked recessive | ≈1 in 5,000 male births | rFVIII or plasma‑derived FVIII |

| Hemophilia B | Factor IX | X‑linked recessive | ≈1 in 30,000 male births | rFIX or plasma‑derived FIX |

| von Willebrand Disease | von Willebrand factor (VWF) | Autosomal dominant (most types) | ≈1 in 100 individuals | Desmopressin or VWF‑containing concentrates |

Related Concepts and Emerging Technologies

Beyond classic factor replacement, several non‑factor therapies have reshaped the landscape. Emicizumab a bispecific antibody that mimics Factor VIII activity, allowing sub‑cutaneous dosing offers weekly or monthly prophylaxis for both hemophilia A patients with and without inhibitors. Meanwhile, CRISPR‑Cas9 editing is being explored to permanently correct F8 mutations in stem cells-still experimental but promising.

Future Directions: Toward Universal Access

While high‑income nations enjoy near‑daily prophylaxis, the global burden remains uneven. Initiatives like the WFH’s “Joint Effort” aim to lower factor costs through pooled procurement and biosimilar entry. Researchers also advocate for decentralized gene‑therapy manufacturing to reach remote clinics. The ultimate goal, echoed by patients and clinicians alike, is a world where a hemophiliac can live without fearing a hidden bleed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is hemophilia called the "royal disease"?

The nickname arose because Queen Victoria’s descendants in several European royal families carried the gene, producing high‑profile cases like Prince Leopold and Tsarevich Alexei, which drew public attention.

What is the difference between Hemophilia A and B?

Hemophilia A lacks clotting factor VIII, while Hemophilia B lacks factor IX. Both are X‑linked recessive, but A is about six times more common and has slightly different treatment products.

How do recombinant factors improve safety?

Recombinant factors are manufactured in cultured cells, eliminating the need for human plasma. This removes the risk of blood‑borne viruses such as HIV or hepatitis C that plagued earlier plasma‑derived products.

What are inhibitors and how are they managed?

Inhibitors are antibodies that neutralize infused clotting factors, making standard therapy ineffective. They are measured with the Bethesda assay. Management includes bypassing agents, immune tolerance induction, or newer non‑factor drugs like emicizumab.

Is gene therapy a cure for hemophilia?

Current gene‑therapy trials achieve long‑term factor expression that can convert severe disease to a mild phenotype, but durability beyond a decade and universal access remain under study. It’s a functional cure for many, not an absolute eradication.

Understanding the hemophilia history helps us appreciate how a condition once whispered only in palace corridors has become a model for precision medicine, patient advocacy, and global health collaboration.

It's sobering to see how far hemophilia treatment has come from royal tragedies to modern biotech. The shift from plasma to recombinant factors saved countless lives. Still, access gaps remain a big challenge.

Ah, the romance of "royal disease"-nothing says aristocratic glamour like a bleeding disorder that turns dynastic courts into medical case studies. One can almost hear the hushed whispers of Victorian courtiers lamenting the inevitable demise of Prince Leopold while sipping tea. Yet, it was precisely that melodramatic backdrop that propelled the early 20th‑century physicians into a frenzy of discovery. They stared at the blood‑soaked floors of royal palaces and thought, "If only we could isolate the missing factor, the world would be a better place." Fast forward to the 1930s, and you have a parade of labs clutching petri dishes, convinced that Pasteur himself would salute their progress. The introduction of plasma‑derived concentrates was hailed as a miracle, albeit one that also introduced the charming surprise of viral infections. HIV and hepatitis sneaked into the treatment pipeline like uninvited guests at a royal banquet, reminding us that even the most noble intentions can have dark side effects. Then came the recombinant era, where scientists proclaimed they had finally banished the specter of blood‑borne pathogens. The industry celebrated with champagne, while patients finally got to breathe without fearing an invisible assassin lurking in their IV bags. But the story does not end with clean proteins; the specter of inhibitors looms like a rogue heir refusing the throne. Up to thirty percent of severe hemophilia A sufferers develop antibodies that neutralize the very therapy meant to save them, a twist worthy of Shakespeare. Management of these inhibitors involves bypassing agents, immune tolerance protocols, and now, the dazzling entry of bispecific antibodies like emicizumab. And just when we thought we had tamed the beast, gene therapy strutted onto the stage, promising a functional cure with a single infusion. Early phase‑III data suggest sustained factor VIII levels that transform severe disease into something resembling a mild inconvenience. Yet, the lingering questions about durability, cost, and equitable distribution keep the narrative as thorny as the royal lineage that started it all.

Wow, from palace gossip to CRISPR labs-what a ride! 🎨 The hemophilia saga reads like a Netflix thriller, complete with betrayals (viral outbreaks), plot twists (inhibitors), and a hopeful ending (gene therapy). If only every disease had such dramatic flair.

look man the whole royal drama is just a excuse to sell more pharma cash lol its not about nobles its about profit and you cant ignore that just read the stats

Hemophilia history is heartbreaking.

Honestly, this whole glorification of "progress" is a smokescreen for the pharmaceutical industry's greed. They parade recombinant factors as miracles while keeping prices sky‑high for people who need them.

the data shows costs have risen despite cheaper tech it’s a profit-driven model not patient care

The evolution from crude plasma to sleek gene‑editing feels like moving from horse‑drawn carriages to hyper‑loop rockets-utterly transformative.

Let's be real, the “miracle cures” touted by biotech are rarely as pure as the press releases suggest. Behind every recombinant factor lies a labyrinth of patents, middlemen, and shadowy lobbyists pulling strings. The CDC and WHO report that in low‑income nations, less than 15% of hemophiliacs even get regular prophylaxis. That statistic isn’t a typo; it’s a stark reminder that the golden age of treatment is a privilege, not a right. Add to that the fact that the same companies pushing gene therapy also fund the very regulatory agencies that approve it. Conflict of interest? Absolutely, and it fuels a narrative that the cure is just around the corner, keeping patients hopeful but penniless. Moreover, the long‑term safety data for AAV vectors is still sketchy-what happens after a decade? Some early trials hinted at liver enzyme spikes, a detail conveniently buried in supplementary tables. And while we applaud the 30‑IU/dL factor levels achieved, we ignore the massive upfront cost that could bankrupt a national health system. The distribution model-centralized, high‑tech infusion centers-means remote villages stay stuck in the dark ages of care. If the industry truly cared, they'd invest in decentralized production, perhaps even open‑source gene constructs. Instead, they lock down intellectual property tighter than the royal vaults that started this whole mess. So before we crown gene therapy as the savior, let’s ask who profits and who pays. The truth is messy, the science wonderful, but the economics are a cautionary tale of capitalism over compassion. Until equitable access becomes the norm, the story of hemophilia will remain a saga of privilege masquerading as progress.

Great overview! It's encouraging to see how far we've come and how many people are pushing for wider access.

Indeed, the journey from the royal corridors to modern laboratories is nothing short of a breathtaking odyssey, replete with triumphs, tragedies, and the relentless pursuit of hope; each milestone a testament to human resilience, perseverance, and the indomitable spirit that refuses to be silenced by the specter of bleeding!

Oh my goodness, reading this feels like watching a historic drama unfold, complete with royal intrigue, scientific breakthroughs, and a dazzling finale of gene therapy-truly a masterpiece of medical evolution!

Totally agree 😄 the way hemophilia treatment has evolved is inspiring, and the future looks bright with all the new tech coming up 🚀💉

The article does a solid job summarizing the timeline, but it could have delved deeper into the socio‑economic barriers that still limit treatment in many parts of the world.

yeah the economics are huge problem we need more affordable options

While the advancements in hemophilia therapy appear commendable, one must consider the possibility that certain data have been selectively presented to conceal underlying conflicts of interest within the pharmaceutical sector.

Surely the science speaks for itself the results are clear and impressive

Honestly, this whole piece reads like a PR brochure-glorifying breakthroughs while glossing over the gritty reality that most patients still suffer from lack of access.

Wow, that’s a bold claim but the facts don’t lie – many still wait for basic factor replacement, so the hype is a bit over the top.

Thank you for this thorough historical account; it not only highlights scientific progress but also underscores the cultural shifts that have empowered patient advocacy worldwide.