How Generic Drug Payments Are Really Set - And Why It Matters to You

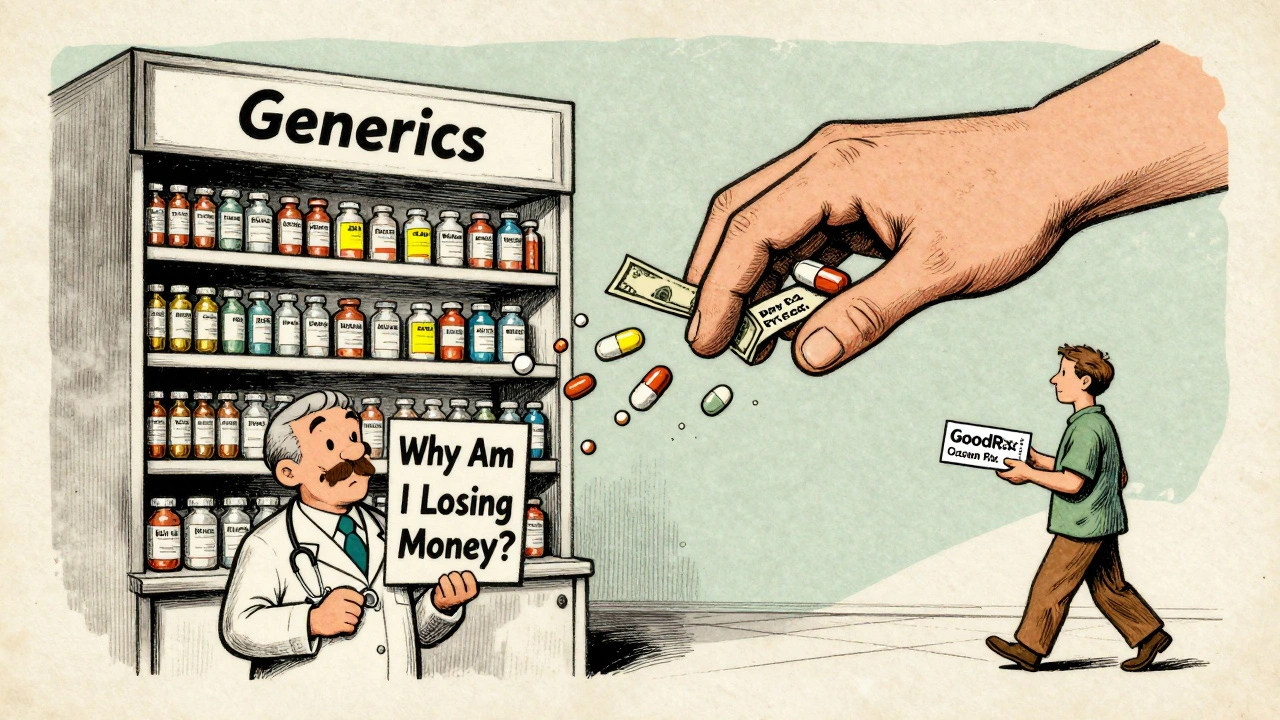

If you’ve ever picked up a generic prescription and been surprised by the price - or worse, told you can’t switch to a cheaper version - you’ve felt the impact of pharmacy reimbursement laws. These aren’t just backroom deals. They’re rules written by Congress, enforced by states, and shaped by giant middlemen called pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). And they directly control how much pharmacies get paid for the pills you take every day.

The system was built to save money. Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the promise: same medicine, lower cost. But the way pharmacies get paid for those generics? It’s anything but simple. And the gap between what a drug costs and what a pharmacy receives can be razor-thin - sometimes just pennies per pill.

The Two Big Ways Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

There are two main reimbursement models for generic drugs: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). Most people don’t know the difference, but it makes a huge difference to your pharmacist - and your wallet.

AWP used to be the standard. It’s a list price published by drug manufacturers, often inflated and not tied to what pharmacies actually pay. Insurers would reimburse pharmacies by subtracting a percentage - say, 20% - from that AWP. But because AWP doesn’t reflect real-world costs, it became unreliable. Today, it’s mostly used for brand-name drugs still under patent.

MAC is what drives generic payments now. It’s a cap set by PBMs or state Medicaid programs - the most a pharmacy will get paid for a specific generic drug, no matter what the pharmacy paid for it. If a pharmacy buys a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril for $8 but the MAC is $6, the pharmacy loses $2. That’s not a profit. That’s a loss. And it happens more often than you think.

Independent pharmacies, especially small ones, are hit hardest. In 2023, the average profit margin on generic drugs was just 1.4%. Five years earlier, it was 3.2%. Many can’t survive on that. That’s why some pharmacies now ask you: “Would you rather pay cash?” - because sometimes, the cash price is lower than your insurance copay.

How Laws Force (or Block) Generic Substitution

Every state has laws about whether a pharmacist can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug. Most allow it - unless the doctor says “dispense as written.” But that’s just the beginning.

Some states go further. They require pharmacists to inform patients when a cheaper generic is available - even if the brand was prescribed. Others ban “gag clauses,” which used to prevent pharmacists from telling you a drug might cost less if you paid out-of-pocket. Those clauses were outlawed in 2018 after years of complaints from consumer groups.

But here’s the catch: even when substitution is allowed, your insurance plan might not pay for it. Medicare Part D plans, for example, often have tiered formularies. Generics are usually on Tier 1 - lowest cost. But if your plan doesn’t include the specific generic you need, or if it’s on a non-preferred list, you could end up paying more than if you’d taken the brand.

And it’s not just about availability. Some plans require prior authorization before you can get even a basic generic. In 2022, 28% of Medicare Part D plans required prior auth for at least one generic drug. That means your doctor has to fill out paperwork, wait for approval, and you might go days without your medication.

Who Really Controls the Prices? PBMs and Their Hidden Fees

Behind every reimbursement rate is a pharmacy benefit manager - CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, or OptumRX. These three companies handle over 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S. They don’t make drugs. They don’t dispense them. But they decide how much pharmacies get paid.

PBMs negotiate rebates with drug makers. They then set reimbursement rates for pharmacies. But here’s the twist: they often keep the difference between what the insurer pays and what the pharmacy gets. That’s called “spread pricing.”

Let’s say your insurer pays $15 for a generic drug. The pharmacy’s actual cost is $5. The PBM pays the pharmacy $8 and keeps $7. That $7 isn’t disclosed to you or your doctor. It’s hidden in the contract. And it’s one reason drug list prices keep rising - manufacturers raise prices to cover the rebates they’re forced to give to PBMs.

Independent pharmacies have no power to negotiate. They either accept the PBM’s terms or get kicked off the network. That means if you go to a local pharmacy, you’re stuck with whatever rate the big PBM decides to pay.

Medicare’s $2 Drug List: A Real Change Coming in 2025

In 2025, Medicare is testing something new: the $2 Drug List Model. It’s simple - for about 100 to 150 essential generic drugs, Part D beneficiaries will pay no more than $2 per prescription, no matter their plan.

The drugs on this list aren’t random. They’re chosen based on three things: how often they’re used by Medicare patients, whether they’re recommended in national treatment guidelines, and whether they’re already on preferred formulary tiers. Think metformin, levothyroxine, lisinopril, atorvastatin - the everyday medicines millions rely on.

This model was inspired by grocery store pharmacies like Walmart and Costco, which have long offered $4 generics. But now, Medicare is bringing that model to its own program. If it works, it could cut out the middleman entirely and put savings directly in patients’ hands.

It’s also a response to the Inflation Reduction Act, which caps insulin at $35 and sets a $2,000 annual out-of-pocket limit for all Part D drugs in 2025. The $2 list is the next step - making the most common generics truly affordable.

Why This All Matters to Patients - and Pharmacists

For patients, this isn’t just about price. It’s about access. If a pharmacy loses money on generics, they may stop stocking them. Or they might stop accepting certain insurance plans. You might have to drive farther, wait longer, or pay more just to get your blood pressure medicine.

For pharmacists, it’s a daily struggle. They’re caught between laws, contracts, and patient expectations. They’re expected to be experts on drug interactions, insurance rules, and cost-saving options - but often aren’t paid enough to cover the time it takes.

And the pressure is growing. Generic drug prices are falling an average of 5-7% per year. Meanwhile, operating costs - rent, staff, compliance - keep rising. Pharmacies are being squeezed from both sides.

But there’s hope. The $2 Drug List could be a turning point. If it proves that patients stick to their meds when costs are predictable, it could change how all of us pay for prescriptions - not just for Medicare, but for commercial plans too.

What You Can Do Right Now

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a cheaper way to get this?” - especially if your copay is over $10.

- Check if your drug is on your plan’s formulary. If it’s not preferred, ask your doctor if another generic is covered.

- Use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices. Sometimes, paying cash beats insurance.

- If you’re on Medicare, look up your plan’s formulary online. See which generics are on Tier 1.

- Speak up. If you’re paying too much for a generic, tell your insurer or your elected representative. Patient pressure changed the rules before - it can again.

The system isn’t broken - it’s working exactly as designed. But the design was never meant to put pharmacists in the red or patients in debt. Real reform is happening. The question is whether it will come fast enough.

Why is my generic drug more expensive than the cash price?

Your insurance plan may have a high deductible or copay structure that makes the out-of-pocket cost higher than the pharmacy’s actual cash price. This often happens with MAC pricing - your insurer pays a fixed amount, but the pharmacy’s cost is lower. Paying cash bypasses the insurance reimbursement system entirely, so you pay the real wholesale price.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug to a generic without asking me?

In most states, yes - unless your doctor wrote “dispense as written” on the prescription. Pharmacists are legally allowed to substitute an FDA-approved generic if it’s therapeutically equivalent. But they’re not always required to tell you. That’s why asking about cost savings is important.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

A generic is made by a different company than the brand. An authorized generic is made by the brand-name company itself - often on the same production line - and sold under a different label. They’re identical in active ingredients, but authorized generics can delay competition because they’re the only generic on the market for a while, reducing price pressure.

Why do some pharmacies refuse to accept my insurance for generics?

If the reimbursement rate set by your PBM is below what the pharmacy paid for the drug, they lose money on every fill. Many independent pharmacies can’t afford to absorb those losses, so they stop accepting certain plans - especially those with low MAC rates or high administrative burdens.

How will the Medicare $2 Drug List affect me if I’m not on Medicare?

Even if you’re not on Medicare, the $2 Drug List could influence commercial insurers. If it proves successful - improving adherence and lowering costs - private plans may follow suit. Some employers and Medicaid programs are already watching closely. It’s a test case for how to make generics truly affordable across the board.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Payments?

The future of generic reimbursement is uncertain - but it’s changing fast. The FTC is cracking down on “pay-for-delay” deals where brand companies pay generic makers to delay entering the market. States are passing laws to regulate PBMs and require transparency in pricing. And Medicare’s $2 model could become permanent.

One thing is clear: the old system - where profits depended on hidden spreads and inflated list prices - is crumbling. The next phase will be about value, not volume. Pharmacies will need to be paid fairly. Patients will need clear, predictable costs. And generics - the backbone of affordable care - will finally get the support they deserve.

Pharmacists are the unsung heroes of healthcare. They know your name, your history, your worries. And yet, they're being forced to choose between staying in business and doing what's right for you. That's a moral crisis.

Let's not forget: generics are safe. They're tested. They're identical. The only difference is the price tag-and who's profiting from it.

Thank you for writing this. I wish every politician had to work a shift here before voting on drug policy.

Also, I just used GoodRx for my blood pressure pill and paid $3 cash. Insurance wanted $22. I’m never using it again. 😅

Don’t just ask your pharmacist. Ask your senator. Write a letter. Call. Show up. This isn’t a policy issue. It’s a human rights issue.