GERD Symptom Risk Calculator

This tool estimates your GERD symptom frequency based on smoking habits and other factors. Results are based on medical studies showing how tobacco impacts the lower esophageal sphincter and acid production.

Your Smoking Habits

Additional Factors

Your GERD Symptom Risk

Heartburn Frequency

Regurgitation Frequency

Quick Takeaways

- Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter, letting stomach acid splash back into the esophagus.

- Nicotine and carbon monoxide both increase acid production and delay stomach emptying.

- Smokers are up to 40% more likely to experience severe heartburn and develop Barrett's esophagus.

- Quitting smoking can reduce reflux episodes within weeks and improve medication response.

- Combining lifestyle changes with proper meds offers the best relief for GERD sufferers who smoke.

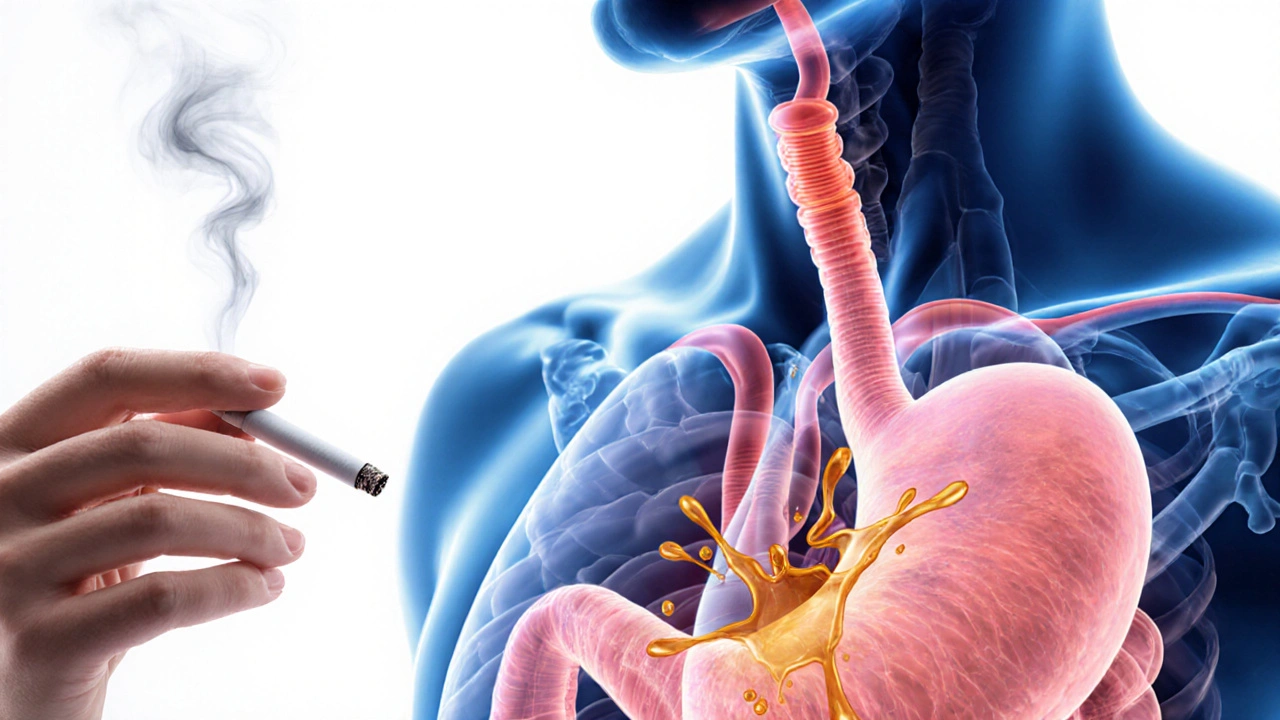

Ever wonder why that occasional heartburn feels like a full‑blown fire after a cigarette? The link between tobacco and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) isn’t just a coincidence - it’s a biochemical tug‑of‑war that plays out every time you light up.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) is a chronic condition where stomach acid repeatedly flows back into the esophagus, causing irritation and a range of uncomfortable symptoms. While diet, obesity, and hiatal hernia get most of the spotlight, smoking is a silent aggravator that many overlook.

What Exactly Is GERD?

Think of your esophagus as a stretchy tube that moves food down to the stomach. At the bottom sits a muscular ring called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). When the LES is tight, it acts like a door, keeping acidic stomach contents where they belong. In GERD, that door is either weak or opens at the wrong times, allowing acid to splash up and burn the lining of the esophagus.

Typical symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, chest discomfort, chronic cough, and even a sour taste in the mouth. If left unchecked, the constant irritation can lead to complications such as Barrett's esophagus, a precancerous change in the esophageal lining.

How Smoking Fuels the Fire

Smoking introduces more than 7,000 chemicals into your throat and lungs. Two of the biggest troublemakers for GERD are nicotine and carbon monoxide.

- Nicotine relaxes smooth muscle, which directly weakens the LES. Studies show LES pressure drops by up to 30% after just one cigarette.

- Carbon monoxide reduces oxygen delivery to the stomach lining, slowing gastric emptying. A slower stomach means more acid sits around, increasing the chance of a back‑flow.

- The heat and irritation from smoke also inflame the esophageal mucosa, making it more sensitive to acid.

In addition, smoking raises overall gastric acid production. A 2023 clinical trial measured a 15% rise in acid output among daily smokers compared with non‑smokers.

Symptoms That Get Worse When You Smoke

Not all GERD sufferers feel the same way, but smokers often report a distinct pattern:

- More frequent heartburn episodes, especially after meals.

- Regurgitation that’s sourer and appears sooner after eating.

- Chronic throat clearing or a lingering cough that doesn’t respond to typical cough medicines.

- Worsening of nighttime symptoms, leading to disrupted sleep.

Why does this happen? The combination of LES relaxation and delayed stomach emptying creates a perfect storm. Every puff nudges the LES further open, so the acid has a clearer path upward.

What Happens When You Quit?

Good news: the body starts repairing itself relatively quickly. Within two weeks of quitting, many former smokers notice a drop in the number of reflux episodes. A 2022 longitudinal study followed 300 GERD patients who quit smoking and found:

- LES pressure improved by an average of 12 mmHg after 4 weeks.

- Heartburn severity scores fell by 35% at the 8‑week mark.

- Use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) was reduced by 20% on average.

Those numbers prove that quitting isn’t just good for your lungs - it gives the esophagus a fighting chance.

Managing GERD If You’re Still Smoking

Quitting isn’t always immediate, and some people need to manage symptoms while they work on it. Here are practical steps that have real‑world traction:

- Schedule meals: Eat at least 2-3 hours before bed and avoid large meals that stretch the stomach.

- Elevate the head of the bed: A 6‑inch raise helps gravity keep acid down.

- Choose the right meds: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole reduce acid production, while H2 blockers can be useful for quick relief.

- Limit trigger foods: Spicy, fatty, or acidic foods can exacerbate reflux, especially when combined with nicotine.

- Stay hydrated, but avoid large volumes during meals: Water helps dilute acid but gulping too much can increase stomach pressure.

- Consider nicotine replacement: Patches or gum provide nicotine without the harmful smoke, and they have a milder impact on the LES.

Pairing these habits with a gradual tapering plan for cigarettes often yields the best symptom control.

Common Myths About Smoking and GERD

Myth #1: "Coffee is the main culprit, not cigarettes."

While coffee can relax the LES, nicotine’s effect is stronger and more consistent. If you cut coffee but keep smoking, you’ll likely still experience reflux.

Myth #2: "Chewing gum after a meal helps because it increases saliva."

Saliva does neutralize acid, but the act of chewing also stimulates more gastric secretions. For smokers, the benefit is outweighed by the LES‑relaxing effect of nicotine.

Myth #3: "If I take more antacids, I don’t need to quit smoking."

Antacids only neutralize existing acid; they don’t address the root cause-LES dysfunction and excess acid production caused by smoking.

Comparison: Symptom Frequency in Smokers vs. Non‑Smokers

| Symptom | Smokers (≥10 cig/day) | Non‑Smokers |

|---|---|---|

| Heartburn | 6-7 days | 2-3 days |

| Regurgitation | 5-6 days | 1-2 days |

| Nighttime cough | 4-5 nights | 0-1 night |

| Sore throat | 3-4 days | 0-1 day |

| Use of rescue antacids (per week) | 10‑12 tablets | 3‑4 tablets |

The table highlights how smoking amplifies the frequency and intensity of GERD‑related discomfort. It’s a clear visual cue that cutting back can make a noticeable difference.

Next Steps: A Simple Action Plan

- Track your symptoms for one week. Note meals, cigarette count, and reflux episodes.

- Set a realistic quit date within the next 30 days. Use a nicotine‑replacement aid if needed.

- Implement at least three lifestyle tweaks from the list above (e.g., elevate the bed, avoid late‑night meals, switch to low‑acid foods).

- Schedule a check‑in with your GP or gastroenterologist. Discuss whether a short trial of PPIs could help while you quit smoking.

- Re‑evaluate after four weeks. You should see reduced symptom scores and possibly need less medication.

Follow this plan, stay patient, and remember that each cigarette you skip is a win for both your lungs and your esophagus.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does vaping affect GERD the same way as smoking?

Vaping still delivers nicotine, which relaxes the LES. While it eliminates many smoke‑related toxins, studies from 2024 show that regular e‑cig users experience a 20% increase in reflux episodes, slightly lower than traditional cigarettes but still significant.

Can I take antacids while trying to quit smoking?

Yes, antacids can provide short‑term relief, but they don’t replace the need to address the underlying cause. Pair them with a quit‑smoking plan for the best long‑term results.

How long does it take for the LES to recover after I stop smoking?

Most people see measurable improvement in LES pressure within 2-4 weeks, with peak recovery around 3 months. The exact timeline varies based on age, overall health, and how heavily you smoked.

Is there a link between smoking, GERD, and Barrett’s esophagus?

Yes. Smoking doubles the risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus in GERD patients, according to a 2021 cohort study of 12,000 individuals. The combination of chronic acid exposure and tobacco‑induced inflammation drives the changes in the esophageal lining.

Do nicotine patches worsen GERD?

Nicotine patches deliver a steadier, lower dose of nicotine compared to cigarettes, resulting in less LES relaxation. Most patients can tolerate patches without a flare‑up of reflux, but monitoring is advised.

Smoking isn’t just a personal habit; it’s a public‑health violation that fuels GERD and drags down the well‑being of everyone around us. The article nails the science, but the moral takeaway is crystal clear: lighting up is an act of negligence toward your own body and the people who love you. If you care about your health, ditch the cigarettes now and set a responsible example.

The data aligns perfectly with what we know about nicotine’s impact on the lower esophageal sphincter. By lowering LES pressure and increasing acid production, smoking creates a perfect storm for reflux. The tables and studies cited make a compelling case for quitting, especially given the heightened risk of Barrett’s esophagus.

Man, I read that whole thing and I gotta say, it’s like a never‑ending saga of how smoking messes up our guts. First off, nicotine is basically a cheat code for the LES to just chill out, and that’s why you feel that burning after a drag. Then there’s the carbon monoxide thing, which slows down gastric emptying, so you’ve got acid hanging around longer for no good reason. The article even dropped numbers – 15% more acid output in smokers – that’s not a typo or some made‑up hype. I’ve been a smoker my whole life, and I can confirm that the heartburn spikes after I light up, especially after a big meal, which the piece highlighted. It also talked about how within two weeks of quitting you start seeing improvements, and honestly, I’ve felt that after my last quit attempt – the fire was less intense. All those lifestyle tips – elevate the head of the bed, avoid late‑night meals, use nicotine patches – are solid, but the real kicker is the psychological part of dealing with cravings while your stomach is screaming. The long‑term risk of Barrett’s? Yeah, that’s scary, and it’s something we should all think about before we light that next cigarette. Bottom line, the article does a great job of mixing hard data with practical steps, and the only thing missing is a direct call‑out to the tobacco industry for pushing a product that literally sets the inside of our throats on fire. So, to sum up, quit smoking, follow the lifestyle tweaks, and give your esophagus a fighting chance – it’s a win‑win for your lungs and your gut.

Hey there, great rundown on the smoking‑GERD link! 😊 If you’re trying to quit, remember that small, consistent steps make a huge difference. Start by cutting back one cigarette a day, and try using a nicotine patch in the evenings to keep the LES from relaxing too much. Also, elevate that head of the bed by 6‑8 inches – you’ll notice fewer night‑time flare‑ups. Keep tracking your symptoms; seeing progress on paper can be a huge motivator. You’ve got this! 💪

First off, kudos for the thorough explanation – it’s both informative and well‑structured. A few grammar pointers: “the LES‑relaxing effect of nicotine” could be phrased as “the LES‑relaxing effect that nicotine has.” Also, consider using a semicolon in the sentence “Smoking raises overall gastric acid production; a 2023 clinical trial measured a 15% rise…” to separate the two independent clauses. That tiny tweak can improve readability. Overall, the content is solid, and the mixture of bullet points and narrative keeps the reader engaged. Keep up the great work! :)

Listen, the tragedy of modern civilization is that we continue to indulge in self‑destruction while preaching health. The article paints a stark portrait: nicotine is the villain that stealthily corrodes the fortress of the lower esophageal sphincter, and yet we cling to the habit like moths to a flame. One must ask, why do we glorify such a deleterious practice? The answer lies in our collective denial and the seductive allure of corporate‑manufactured addiction.

It is high time we rise above this morass, reject the tobacco industry’s manipulations, and reclaim our bodies from the tyranny of nicotine. The data is irrefutable, the risk is palpable, and the moral imperative is crystal clear. Abstain, endure the withdrawal, and emerge victorious.

The piece does a solid job tying nicotine to LES relaxation and increased acid output. It’s clear that even e‑cigarettes aren’t harmless when it comes to reflux, as they still deliver nicotine that messes with the sphincter.

In the quiet moments before a cigarette, one might wonder if the ember’s glow is a beacon of comfort or a subtle thief stealing the tranquility of the esophagus. The fire within the throat, fueled by nicotine, mirrors the inner turmoil of a soul seeking release.

I get it.

Reading this gives me hope that every small step toward quitting can ripple into massive health gains. Remember, progress isn’t linear – some days you’ll slip, but the overall trend moves upward. Keep the focus on the long‑term payoff: a happier gut, clearer lungs, and a brighter future. You’re on the right path; stay steady and celebrate each win.

In accordance with the presented evidence, it is evident that tobacco consumption exerts a deleterious effect on the lower esophageal sphincter, thereby exacerbating gastro‑esophageal reflux disease. Accordingly, cessation of smoking should be advocated as a primary intervention alongside pharmacologic therapy.