Gallstone Type Identifier

Gallstone Diagnosis Quiz

Answer these questions to determine the most likely type of gallstone you may have.

Gallstones can pop up out of nowhere, cause painful attacks, and often lead people to think surgery is the only way out. But medication plays a surprisingly big role-both for dissolving existing stones and keeping new ones from forming. Below we break down which drugs work, when they’re right, and what you need to watch out for, so you can decide if a pill could spare you an operation.

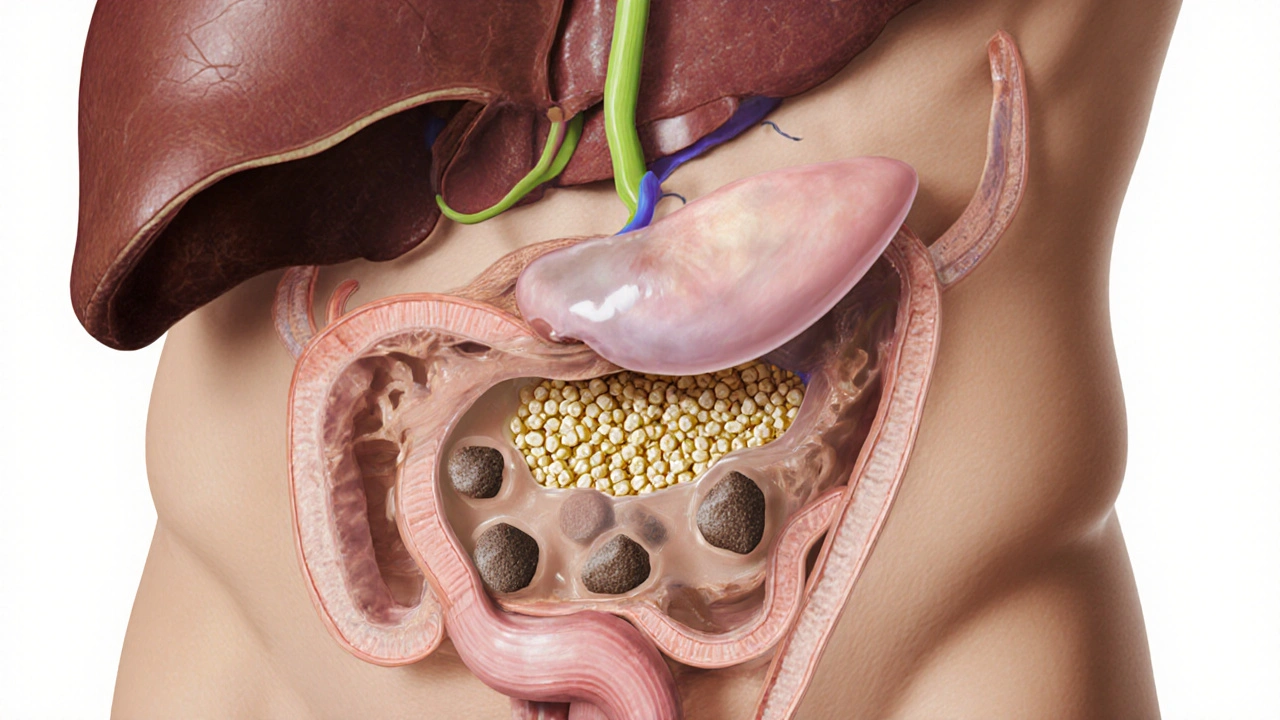

What Exactly Are Gallstones?

Gallstones are hardened deposits that form in the gallbladder, a tiny organ tucked under the liver that stores bile. Most stones are cholesterol gallstones, made mostly of hardened cholesterol, while a smaller share are pigment stones that contain bilirubin. The size can range from a grain of sand to a golf ball, and the impact varies: tiny stones may pass unnoticed, whereas larger ones can block the bile ducts and trigger severe abdominal pain known as biliary colic.

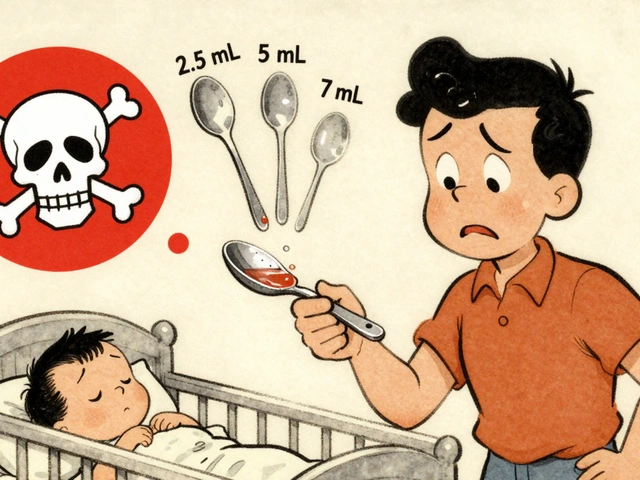

When discussing gallstone pharmacotherapy, one must first acknowledge the biochemical milieu of bile supersaturation; the interplay of cholesterol, bile salts, and phospholipids creates a delicate equilibrium, which, if perturbed, precipitates crystalline nucleation. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) operates by reducing cholesterol saturation, thereby promoting gradual dissolution of cholesterol-dominant calculi; it is not a panacea, however, and its efficacy hinges upon stone size-generally those ≤1.5 cm respond favorably. Moreover, the therapeutic window demands adherence to a regimen spanning six months to two years, during which hepatic enzymes should be monitored biweekly to preempt hepatotoxicity. Patients with pigment stones, derived from bilirubin polymers, rarely benefit from UDCA; alternative agents such as chenodeoxycholic acid may be explored, albeit with caution due to documented side‑effect profiles. Dietary modification complements pharmacologic intervention; a low‑fat, high‑fiber diet reduces gallbladder stasis, mitigating further nucleation events. Weight management is equally paramount, because rapid weight loss-often seen in bariatric programs-exacerbates cholesterol supersaturation, paradoxically increasing stone formation risk. In clinical practice, counseling patients on the balance between surgical cholecystectomy and medical dissolution involves shared decision‑making, weighing recurrence rates, symptom severity, and personal preferences. Studies indicate a recurrence probability of approximately 20 % within five years for those managed medically, versus near‑zero post‑cholecystectomy, though the latter carries operative morbidity. For patients contraindicated to surgery-perhaps due to cardiopulmonary comorbidities-UDCA remains the cornerstone of non‑invasive therapy. Adherence, however, is a behavioral challenge; the once‑daily dosing schedule can be undermined by gastrointestinal upset, prompting clinicians to employ proton pump inhibitors prophylactically. The pharmacokinetics of UDCA are noteworthy: it is absorbed in the small intestine, conjugated in the liver, and excreted into bile, thereby directly targeting the lithogenic environment. In terms of cost‑effectiveness, generic formulations have rendered long‑term therapy financially viable for most insurance plans. Nonetheless, clinicians must remain vigilant for rare complications such as gallstone ileus, which, though primarily surgical, can be precipitated by incomplete dissolution. Ultimately, the decision matrix incorporates stone composition analysis-often inferred from imaging and patient history-laboratory markers, and patient tolerance for medical versus surgical pathways. As research advances, novel agents targeting nucleation inhibitors may soon augment the therapeutic armamentarium, potentially revolutionizing gallstone management.

Gallstones can be a real pain, but knowing that medication exists gives hope for those who dread surgery.

Ah, yes, the marvel of modern medicine: pop a pill and expect the stone to vanish-if only life were so conveniently programmable, one might forget the centuries-old tradition of excising the gallbladder.

Honestly, if our health system wasn’t so tangled in red‑tape, we’d have the best meds for gallstones-no one’s better than us at making a pill work, ya know?

It’s understandable to feel anxious about starting a medication regimen; after all, the prospect of a long‑term pill can feel daunting, yet with proper monitoring, many patients find relief without surgery.

Take UDCA it works but you must stay on it for months

Wow, who knew a tiny capsule could be a superhero for your gallbladder! 🌟💊 Let’s give those stones a run for their money! 🎉

Medication works for small cholesterol stones.

Great news, folks-if you catch the stones early, a simple drug like ursodeoxycholic acid can dissolve them, sparing you the knife and the recovery time!

Well, the literature is unequivocal: bile‑acid therapy yields a modest dissolution rate, yet many overlook the stringent inclusion criteria, thereby misapplying the protocol.

Interesting point about stone composition-have you considered that pigment stones often require a different therapeutic approach, perhaps involving antibiotics for underlying hemolysis?

Honestly, Lauren, your “literature is unequivocal” stance feels a bit over‑blown; most clinicians just prescribe UDCA when the patient asks, not after a deep dive into criteria.

From a global health perspective, access to UDCA varies widely; in low‑resource settings, diet modification remains the primary strategy due to cost constraints.

Sure, let’s all rely on the miracle pill, but don’t forget that lifestyle changes are the unsung heroes that keep the gallbladder happy.

Keep looking at the options-whether it’s meds or diet, there’s always a path forward.

Hutchins, nice try with the “interesting point,” but you missed the fact that pigment stones rarely dissolve with bile acids-maybe check your sources?

In contemplating the delicate equilibrium of biliary chemistry, one discerns a profound metaphor for human existence: balance begets harmony, while excess precipitates disorder, echoing the very genesis of gallstones.

Ah, Kathryn, that poetic take on bile is as refreshing as a stone‑free gallbladder-if only all medical discussions could be so lyrically profound.