When your body’s main hormone control center starts growing a tumor, it doesn’t always cause pain. Often, the first signs are subtle-missed periods, low libido, unexplained milk production, or fatigue that won’t go away. These aren’t just random symptoms. They’re signals from a prolactinoma, the most common type of pituitary adenoma. Unlike cancer, these tumors are benign, but they can throw your entire endocrine system out of balance. And because the pituitary gland sits right at the base of your brain, even a small growth can press on nerves, vision, or hormone pathways without you realizing it until things get serious.

What Exactly Is a Prolactinoma?

A prolactinoma is a noncancerous tumor in the pituitary gland that makes too much prolactin. This hormone normally helps with breast milk production after childbirth. But when it’s overproduced outside of pregnancy, it shuts down other hormones-like estrogen and testosterone-that control fertility, sex drive, and energy. About 40 to 60% of all pituitary adenomas are prolactinomas, making them the most frequent hormone-secreting tumor you’ll find in this area. Most are small-under 1 centimeter-and called microadenomas. But when they grow larger than 1 cm, they become macroadenomas, and that’s when problems like vision loss or headaches start showing up.

Women with prolactinomas often notice amenorrhea (no periods), galactorrhea (milky discharge from breasts when not nursing), or trouble getting pregnant. Men might experience low testosterone symptoms: reduced body hair, erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, or even breast enlargement. In both sexes, fatigue, weight gain, and mood swings are common. And here’s the catch: many people go years without diagnosis because these symptoms get mistaken for stress, depression, or aging.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Diagnosing a prolactinoma isn’t complicated, but it requires specific tests. First, your doctor checks your blood for prolactin levels. Normal levels are under 20 ng/mL for women and under 15 ng/mL for men. If your level is over 150 ng/mL, there’s a 95% chance it’s a prolactinoma. Levels above 200 ng/mL almost always mean a macroadenoma. But don’t jump to conclusions-some medications (like antidepressants or antipsychotics), kidney failure, or even pregnancy can raise prolactin too. So your doctor will rule those out first.

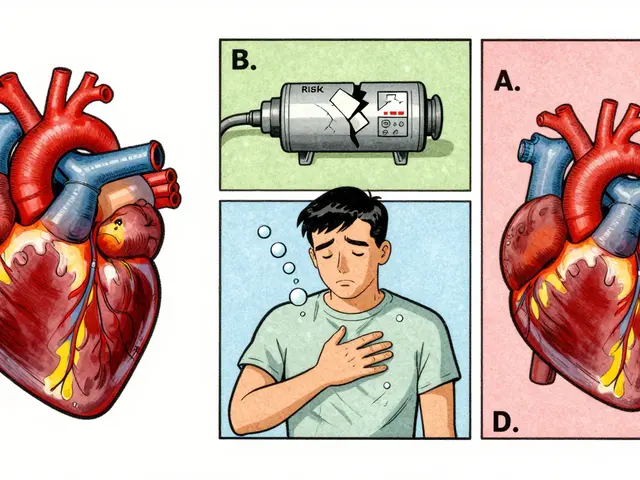

The next step is an MRI of your brain, specifically with 3mm slices to catch even tiny tumors. A standard head MRI won’t cut it-you need a pituitary-focused scan. If the tumor is bigger than 1 cm, you’ll also need a visual field test. That’s because the optic nerves sit right above the pituitary gland. A growing tumor can squeeze them, causing blind spots in your peripheral vision. Left untreated, that can lead to permanent vision loss.

First-Line Treatment: Dopamine Agonists

The go-to treatment for prolactinomas isn’t surgery-it’s medicine. Dopamine agonists like cabergoline and bromocriptine trick your brain into thinking there’s enough prolactin, so the tumor stops producing it. Cabergoline is the preferred choice. It’s taken just twice a week, works better, and causes fewer side effects than bromocriptine, which needs daily dosing and often causes nausea, dizziness, or low blood pressure.

Studies show cabergoline normalizes prolactin in 80-90% of microadenomas and about 70% of macroadenomas within three months. Tumors shrink in 85% of cases. One Mayo Clinic case followed a 34-year-old woman with a 2.4 cm tumor and prolactin levels of 5,200 ng/mL. After six months on cabergoline (1 mg twice weekly), her levels dropped to 18 ng/mL and the tumor shrank by 70%. That’s not an outlier-it’s standard.

But here’s what most patients don’t realize: you can’t just stop taking cabergoline. If you miss doses, prolactin spikes back up within 72 hours. And in about 70% of cases, you’ll need to stay on it long-term-even if the tumor disappears. Some patients stay on it for years. The good news? Most tolerate it well. Only 18% quit cabergoline due to side effects, compared to 32% who quit bromocriptine.

When Is Surgery Needed?

Surgery isn’t the first option-but it’s critical when medicine fails or vision is at risk. The standard procedure is transsphenoidal surgery, where the surgeon reaches the pituitary through the nose or upper lip. Endoscopic techniques (using a tiny camera) are now the norm, reducing recovery time to 3-5 days. Success rates are high for small tumors: 85-90% of microadenomas are fully removed. But for macroadenomas, especially those that have spread into the cavernous sinus, success drops to 30-50%. Recurrence rates climb to 25-30% within five years.

Surgery carries real risks: cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks happen in 2-5% of cases, diabetes insipidus (a condition causing extreme thirst and urination) in 5-10%, and pituitary apoplexy (sudden bleeding into the tumor) in 1-2%. Some patients need temporary or lifelong hormone replacement after surgery if the gland is damaged. Still, many who’ve had surgery report high satisfaction-82% on patient forums say they’re glad they did it, especially if they had vision problems or couldn’t tolerate meds.

Radiation Therapy: A Last Resort

Radiation is rarely used today unless the tumor keeps growing after surgery and medicine doesn’t work. It’s slow. It can take two to five years to lower prolactin levels. And while it controls tumor growth in 95% of cases with Gamma Knife radiosurgery, it often damages healthy pituitary tissue. About 30-50% of patients develop hypopituitarism-meaning their gland stops making other vital hormones like cortisol, thyroid hormone, or growth hormone. That means lifelong replacement therapy.

Gamma Knife delivers a single, precise dose of radiation with less than 2% risk to the optic nerve. Traditional radiation (fractionated beams over weeks) has a 5-10% risk of damaging vision. Proton beam therapy is newer and even more targeted, but it’s only available at major centers and costs more. Radiation isn’t something you choose lightly. It’s a long-term commitment with delayed results and potential lifelong side effects.

What About Long-Term Risks?

Cabergoline is safe for most, but high doses-over 2.5 mg per week for more than three years-can cause heart valve thickening in 2-7% of people. That’s why the European Society of Endocrinology recommends an echocardiogram after one year of treatment if you’re on more than 2 mg per week, and then every two years after that. The FDA hasn’t banned cabergoline, but it added a black box warning for this risk.

There’s also the emotional toll. Living with a chronic condition, even a treatable one, can be isolating. Many patients feel embarrassed about symptoms like galactorrhea or low libido. Support groups, like those on Reddit’s r/pituitary, help. One survey of 1,245 patients found that 78% saw symptom improvement within 4-6 weeks of starting cabergoline. That’s powerful relief for people who’ve been struggling for years.

What’s Next in Treatment?

The future is looking promising. In 2023, the FDA approved paltusotine for acromegaly-a related pituitary disorder-and early trials are testing it for prolactinomas. Researchers are also exploring CRISPR gene editing to target mutations like MEN1 that cause these tumors. AI is being used to help surgeons plan the safest path through the skull. And new molecular markers (like GNAS and USP8 mutations) are helping doctors predict which tumors are more aggressive.

Dr. Maria Fleseriu predicts that within five years, we’ll use genetic profiling to pick the best treatment for each patient-boosting cure rates from 70% to 90%. But for now, the basics still work: accurate diagnosis, dopamine agonists first, surgery when needed, and lifelong monitoring.

What You Need to Know

- If you’re a woman with unexplained missed periods or milk production, get your prolactin checked-even if you’re not pregnant.

- If you’re a man with low sex drive, fatigue, or breast tenderness, don’t assume it’s just aging. Ask about hormone levels.

- Cabergoline is the most effective, easiest-to-take option. Stick with it. Missing doses makes it useless.

- Don’t delay an MRI if your prolactin is over 150 ng/mL. Vision damage can be permanent.

- Surgery is effective for small tumors, but not a guaranteed cure for large ones.

- Radiation is slow and risky-only consider it if other options fail.

- Get regular follow-ups. Even after prolactin normalizes, you need annual checks to catch recurrence early.

Can a prolactinoma go away on its own?

Rarely. Most prolactinomas don’t shrink without treatment. In a small number of cases-usually microadenomas under 1 cm-prolactin levels may drop slightly over time, but the tumor usually remains. Waiting isn’t safe. Untreated tumors can grow, damage vision, or cause permanent hormone loss. Treatment isn’t optional-it’s necessary to prevent complications.

Can I get pregnant if I have a prolactinoma?

Yes, but only after treatment. High prolactin stops ovulation. Once prolactin levels drop with cabergoline, fertility usually returns within weeks. Many women conceive within three to six months of starting treatment. Doctors often lower the dose during pregnancy, but most patients stay on a low dose to keep the tumor from growing. Regular monitoring is essential.

Is cabergoline safe for long-term use?

For most people, yes. Side effects like nausea or dizziness usually fade after a few weeks. The main concern is heart valve thickening with high doses (over 2.5 mg/week) over three years. That’s why doctors recommend an echocardiogram after one year if you’re on higher doses, then every two years. For the vast majority on standard doses (0.5-1 mg twice weekly), the risk is extremely low. The benefits of normalizing hormones and shrinking the tumor far outweigh the risk.

Do I need to see a specialist?

Absolutely. Pituitary adenomas require expertise. Endocrinologists manage the hormone side, neurosurgeons handle surgery, and radiation oncologists oversee radiation. Community doctors often miss the diagnosis because these tumors are rare. If you’re diagnosed, ask for a referral to a pituitary center-places like Mayo Clinic, MD Anderson, or Massachusetts General have teams that handle 150+ cases a year. They know the latest protocols and can adjust treatment faster.

Can stress cause a prolactinoma?

No. Stress can raise prolactin temporarily, but it doesn’t cause tumors. Prolactinomas arise from genetic mutations in pituitary cells-usually random, not inherited. You didn’t cause this. You didn’t do anything wrong. It’s not your fault. The good news? It’s treatable. And with the right care, most people return to normal life.

15 Comments

Write a comment