When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way as your sibling, parent, or cousin-even though you’re taking the exact same pill? The reason might not be the drug itself. It could be your genes.

Why Your Family’s Medical History Matters More Than You Think

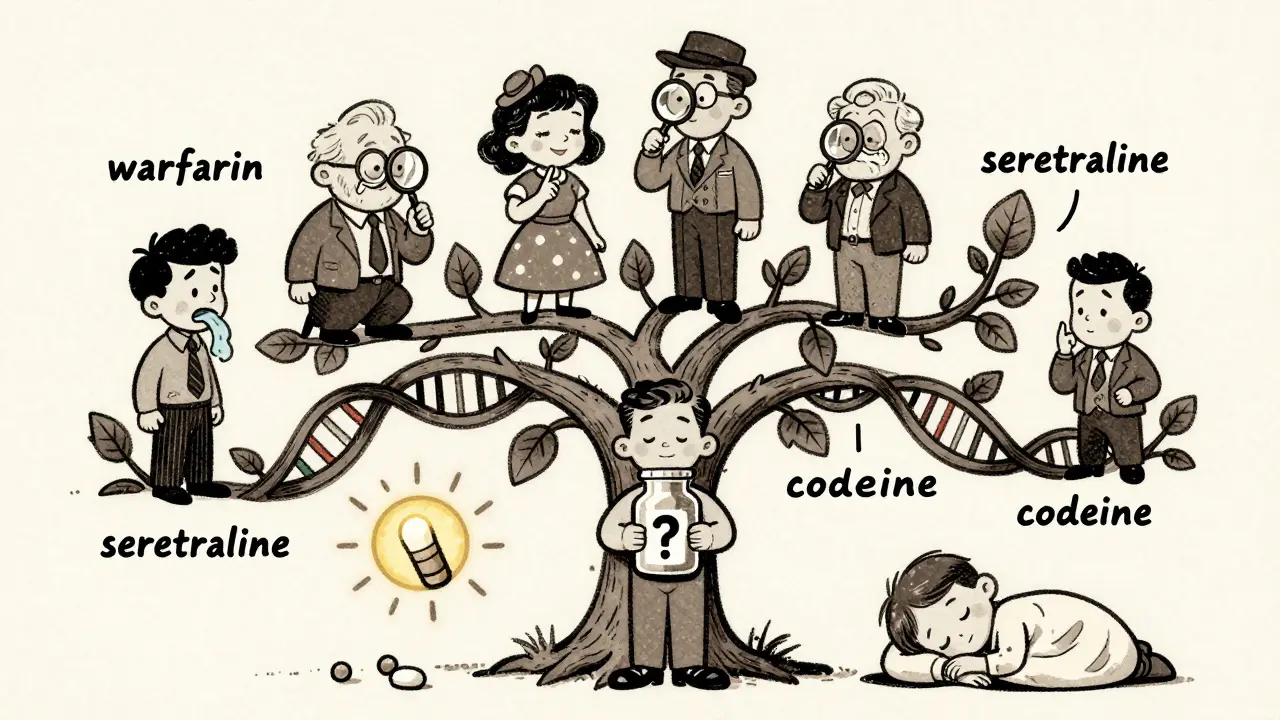

You’ve probably heard that high blood pressure or diabetes runs in your family. But did you know your family’s history with medications matters too? If your mother had a bad reaction to a common painkiller, or your father needed a much lower dose of a blood thinner to stay safe, those aren’t just coincidences. They’re clues written in your DNA. Pharmacogenetics is the science that studies how your genes affect how your body handles drugs. And it’s not theoretical anymore. Over 300 prescription drugs, including generics, now have genetic information listed on their labels by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. That includes common medications like warfarin, clopidogrel, statins, and antidepressants. Your genes control how fast or slow your liver breaks down medicines. If your body processes a drug too quickly, it won’t work well. If it processes it too slowly, the drug builds up and can cause dangerous side effects. These differences aren’t random-they’re inherited. So if your mom was a slow metabolizer of a certain drug, there’s a good chance you are too.The Genes That Control How Your Body Handles Medicines

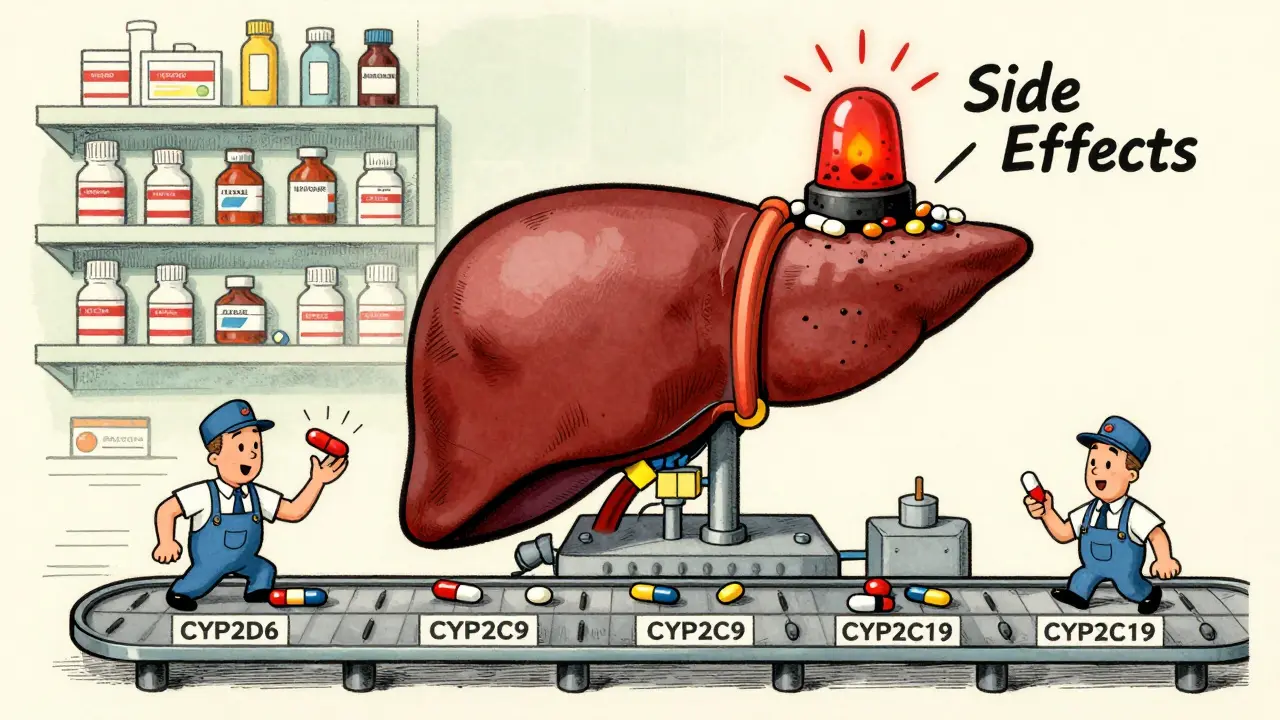

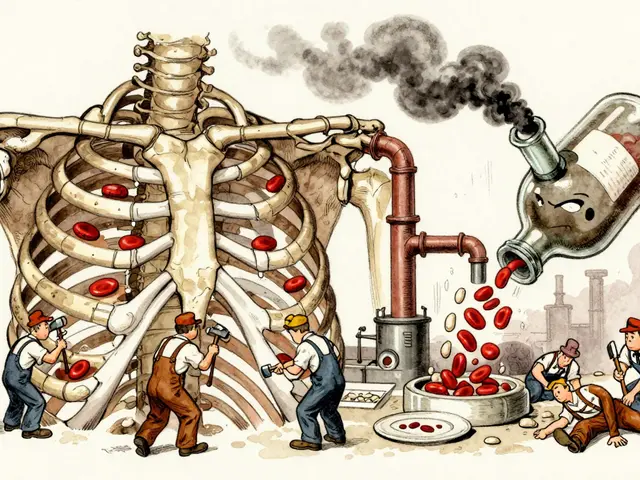

Not all genes matter equally when it comes to drug response. The most important ones are the cytochrome P450 enzymes, especially CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. These are like your body’s drug-processing factories. CYP2D6 is responsible for breaking down about 25% of all prescription drugs, including common antidepressants like sertraline and paroxetine, and painkillers like codeine. More than 80 different versions of this gene exist worldwide. Some make you a fast metabolizer-you clear the drug so quickly it doesn’t work. Others make you a slow metabolizer-you build up toxic levels even at normal doses. A 2023 study found that 7-10% of people of European descent are slow metabolizers of CYP2D6. That number jumps to 20-25% in some Asian populations. CYP2C9 affects warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent strokes. People with certain variants of this gene need up to 30% less warfarin than average. If you’re given a standard dose, you could bleed internally. In fact, a 2020 study showed that patients with these variants were 4 times more likely to have dangerous bleeding episodes if not genetically tested. CYP2C19 is critical for proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole, used for acid reflux. About 15-20% of Asians are poor metabolizers of this drug, meaning it doesn’t work as well for them. If you’re from Southeast Asia and your reflux meds aren’t helping, your genes might be why. Then there’s TPMT, a gene that controls how your body handles chemotherapy drugs like 6-mercaptopurine. If you have two faulty copies of this gene, even a normal dose can destroy your bone marrow. Testing for TPMT before starting treatment has reduced severe side effects by 90% in children with leukemia, according to research from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.Genetic Differences Between Populations

Your ancestry plays a big role in which gene variants you carry. A 2024 study comparing Tunisian and Italian populations found major differences in how people metabolize statins, metformin, and other common drugs. For example, a variant linked to poor response to pravastatin was far more common in people of Sub-Saharan African descent than in Europeans. This isn’t about race-it’s about genetic ancestry. African Americans, on average, need higher doses of warfarin than white patients because of differences in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes. But blanket dosing by race is outdated. The best approach now is genetic testing, not guesswork. One 2023 clinical trial found that patients who got their warfarin dose adjusted based on genetic testing spent 7-10% more time in the safe therapeutic range than those who didn’t. That’s not a small difference-it means fewer hospital visits, fewer clots, and fewer bleeds.

Real Stories: When Genetics Saved Lives (or Didn’t)

A woman in Sydney, Australia, was scheduled for chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil. Her oncologist ordered a DPYD gene test before treatment. The results showed she carried a dangerous variant that slows drug breakdown. Her dose was cut from 1200mg/m² to 800mg/m². She completed treatment without severe nausea, vomiting, or life-threatening low white blood cell counts. Another patient, a 58-year-old man in Melbourne, had been on sertraline for depression for years. He kept having dizziness, nausea, and heart palpitations. His psychiatrist dismissed it as “side effects everyone gets.” After a $350 GeneSight test showed he was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer, his doctor switched him to a different antidepressant that doesn’t rely on that enzyme. His symptoms vanished within two weeks. But not everyone is so lucky. A 2022 survey of 1,247 clinicians found that 79% said they didn’t have time to review genetic test results. Some doctors still don’t know how to interpret them. One Reddit user shared that after getting a positive result for a dangerous gene variant, his psychiatrist ignored it. He ended up in the hospital with serotonin syndrome.What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for a crisis. If you or a close family member has had unexpected side effects from a medication, or if a drug just didn’t work even at high doses, ask your doctor about pharmacogenetic testing. Here’s what to do:- Write down any family members who had bad reactions to medications-especially blood thinners, antidepressants, or chemotherapy.

- Ask your GP or pharmacist if your current meds have known genetic interactions.

- Request a test for CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 if you’re on any of these drugs: statins, SSRIs, warfarin, clopidogrel, or proton pump inhibitors.

- Look for tests covered by Medicare or private insurance. Some, like those from Color Genomics, cost under $250 and test multiple genes at once.

- Ask if your hospital or clinic has a pharmacogenomics program. Mayo Clinic, Vanderbilt, and several Australian hospitals now offer preemptive testing.

The Future of Generic Drugs and Personalized Medicine

Generic drugs are cheaper because they’re chemically identical to brand names. But identical chemistry doesn’t mean identical results in your body. That’s why the future of generics isn’t just about cost-it’s about matching the right drug to the right person. By 2025, 92% of academic medical centers plan to expand pharmacogenomic testing. The NIH spent $127 million on this research in 2023 alone. The goal? To make genetic testing part of routine care, like checking blood pressure. The FDA has already approved the first antidepressant selection tool guided by genetics. In the next five years, you’ll likely see pharmacogenomic results printed on your pharmacy receipt-just like your dosage instructions. The message is clear: your genes are already affecting how you respond to every pill you take. Ignoring them isn’t just outdated-it’s risky. Whether you’re switching to a generic, starting a new medication, or just wondering why your meds don’t seem to work, your family history might hold the answer. And now, science gives us the tools to read it.Can my family history predict how I’ll respond to generic drugs?

Yes. If close relatives had bad reactions to certain medications-like bleeding on warfarin, severe nausea from chemotherapy, or no effect from antidepressants-your genes may be similar. Family history is a strong signal that genetic testing could be useful. It doesn’t guarantee your response, but it’s a clear reason to investigate further.

Are generic drugs less effective because of genetics?

No. Generic drugs are chemically identical to brand-name versions. The issue isn’t the drug-it’s how your body processes it. Two people can take the same generic pill, and one gets relief while the other has side effects. That’s due to genetic differences, not drug quality.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance in Australia?

Medicare doesn’t yet cover routine pharmacogenetic testing, but it does cover specific tests when ordered for certain high-risk drugs like thiopurines or 5-fluorouracil. Private insurers sometimes cover tests like Color Genomics or OneOme if your doctor shows clinical necessity. Costs range from $200 to $500, and some hospitals offer subsidized testing through research programs.

How long does it take to get genetic test results for drug response?

Most commercial tests take 7-14 days from the time your sample is sent to the lab. Some hospital-based programs, especially in major cities like Sydney or Melbourne, can return results in as little as 3-5 days if the test is flagged as urgent. Results are usually sent to your doctor, who then explains what they mean for your medication plan.

Can I get tested before I even start a new medication?

Yes. This is called preemptive testing. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic and some Australian medical centers now offer panels that test for dozens of gene-drug interactions at once. Once you’re tested, the results stay in your medical record and can guide future prescriptions. You only need to do it once in your lifetime.

Do I need to stop taking my meds before a genetic test?

No. Genetic tests look at your DNA, which doesn’t change based on what drugs you’re taking. A blood or saliva sample is all you need. You can keep taking your medications as usual. The test tells you how your body will process drugs in the future, not how it’s reacting right now.

OMG I had no idea my weird reaction to ibuprofen was genetic! My mom used to say she couldn't take it either-thought it was just 'being sensitive.' Now I'm kinda mad we didn't get tested sooner.

Just ordered a Color Genomics kit. Fingers crossed it explains why Zoloft made me feel like a zombie.

The scientific basis presented here is robust and aligns with current clinical pharmacogenomics literature. The FDA’s inclusion of pharmacogenetic data on over 300 drug labels underscores the transition from empirical prescribing to evidence-based, genotype-guided therapy. While accessibility remains a barrier, the trajectory toward integration into routine care is both inevitable and ethically imperative.

It’s wild to think that the same pill can be a miracle for one person and a nightmare for another-and it’s all because of your family’s biology.

My grandma took warfarin for decades and never bled out. My uncle took it once and ended up in the ER. Now I know why.

We all deserve to know how our bodies work before we swallow something that could hurt us.

Testing shouldn’t be a luxury. It should be standard.

Like getting your blood type before donating.

It’s just common sense.

Ugh, another ‘your genes are destiny’ clickbait article. Let me guess-you’re gonna tell me my depression is just ‘bad CYP2D6’ and I shouldn’t try therapy?

Newsflash: drugs don’t fix your life. They just mask it. And if your ‘genetic test’ is just an excuse to keep taking pills instead of fixing your sleep, diet, trauma, or loneliness-you’re being scammed.

Also, 20% of Asians are poor metabolizers? That’s not genetics, that’s poor diet and pollution. Stop blaming your DNA for bad lifestyle choices.

India has no access to this testing. My cousin took clopidogrel after stent and had a stroke. Doctor said ‘it’s just how it is.’

Now I’m angry. Why does this only matter in rich countries?

😢

my aunt had a bad reaction to statins and they just kept giving her higher doses until she couldn't walk

if they'd just tested her gene first...

why don't doctors just ask about family history before prescribing?

i think they're scared of the paperwork

or they just don't know

or maybe they don't care

but it shouldn't be this hard to stay safe

This is why I started sharing my pharmacogenetic results with my family. My sister just got tested after reading this-turns out she’s a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer too. She’s been on omeprazole for years and never knew it wasn’t working. Now she’s on pantoprazole and her acid reflux is gone.

Knowledge isn’t power-it’s peace of mind.

And it’s contagious.

Bro… my dad died from bleeding on warfarin. No one told us to test. No one even asked about his uncle who died the same way.

Now I’m the only one in the family who got tested.

They think I’m weird.

But I’m the one who’s still alive.

So… yeah.

Test. Your. Genes.

💀

I just got my results back… CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer… that explains why I had to take 3x the dose of sertraline to feel anything… and why I got so sick when I tried codeine…

Why didn't anyone tell me this before I wasted 10 years trying different meds…

I feel like I've been gaslit by the medical system…

and now I'm terrified to start anything new…

what if I'm wrong… what if I'm not…

do I even trust this test…

do I trust my doctor…

do I trust myself…

This is a dangerous oversimplification. Genetic determinism in pharmacology ignores environmental, epigenetic, and socioeconomic factors. You are not your DNA. You are your access to care, your diet, your stress levels, your trust in physicians. To reduce complex human physiology to a SNP panel is not science-it is corporate marketing disguised as innovation. The pharmaceutical industry profits from repeated prescriptions, not from preventative testing. Be wary.

My grandfather was a pharmacist in the 70s. He used to say, ‘If the medicine doesn’t work, it’s not the drug-it’s the person.’ Back then, he had no way to prove it. Now we do. It’s about time.

There’s something beautiful about realizing your body isn’t broken-it’s just different.

My mom thought I was ‘just hard to treat’ for depression. Turns out I just needed a different enzyme pathway.

It’s not failure. It’s alignment.

And once you know your code, you can finally stop guessing.

You’re not broken. You’re coded.

Test your genes. Or keep suffering.

Simple.

Let me tell you about the time I spent six months trying every antidepressant known to man because my doctor said ‘it’s trial and error.’ I was 22, working two jobs, crying in the shower every night, and every pill made me feel worse-except the one that gave me serotonin syndrome and sent me to the ER. I didn’t know about CYP2D6. No one told me. My mom had the same reaction to Prozac. But she never told me because she thought it was ‘just her.’ I finally got tested after a near-death experience. Turns out I’m a slow metabolizer. I switched to bupropion and within two weeks, I slept through the night for the first time in five years. I’m not saying this to be dramatic-I’m saying this because if one person reads this and goes to their doctor and asks for a test, then maybe, just maybe, someone else won’t have to suffer like I did. This isn’t sci-fi. It’s science. And it’s here. And it’s saving lives. And if your doctor doesn’t know about it, bring them this article. Or find a new doctor. Your life is worth more than their ignorance.