Blood Count Risk Assessment Tool

Enter Your Blood Count Values

When you take a medication to treat cancer, an autoimmune disease, or even a stubborn infection, you expect relief-not a dangerous drop in your blood counts. But for many people, the very drugs meant to heal can quietly shut down the bone marrow’s ability to make blood cells. This is medication-related bone marrow suppression, and it’s more common than most patients realize. It doesn’t always come with warning signs. No rash. No nausea. Just a slow, silent decline in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets-until you’re too tired to get out of bed, prone to infections you can’t fight off, or bleeding for no reason at all.

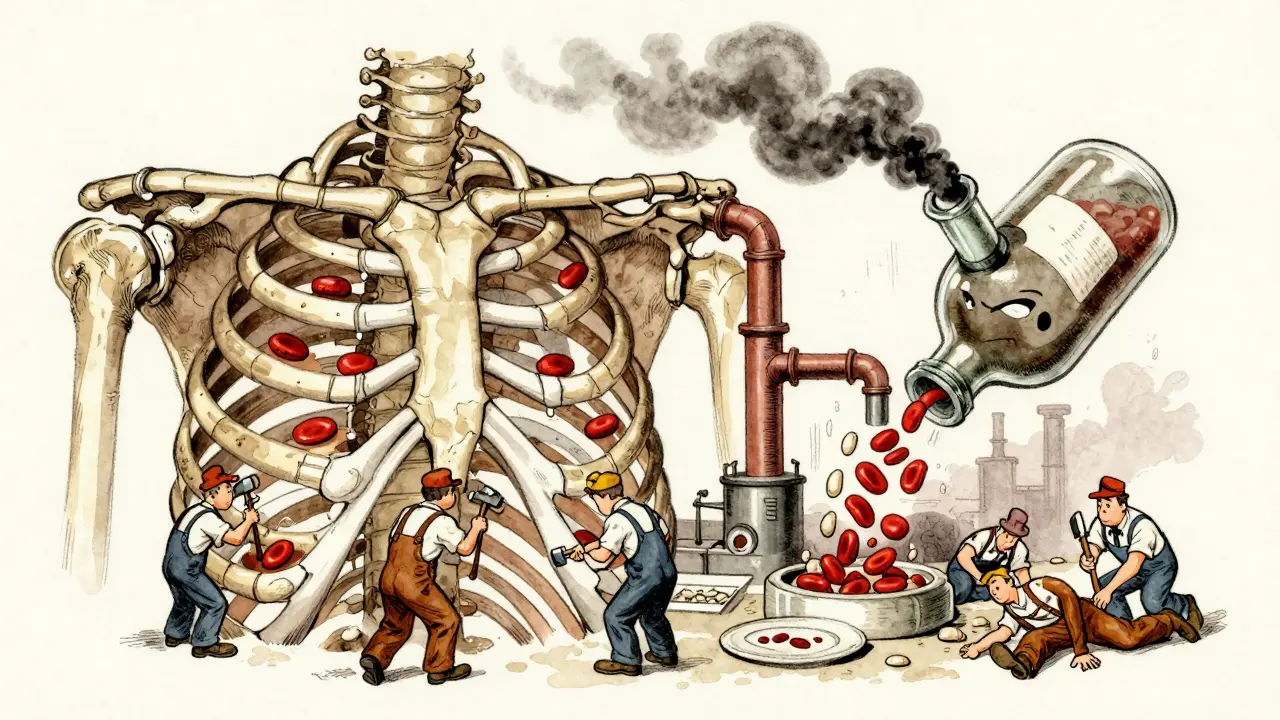

What Exactly Is Bone Marrow Suppression?

Your bone marrow is the factory inside your bones that produces every type of blood cell. Red blood cells carry oxygen. White blood cells fight infection. Platelets stop bleeding. When medications damage this factory, production slows or stops. This is called myelosuppression. It’s not a disease itself-it’s a side effect. And it’s not rare. About 60 to 80% of people on standard chemotherapy experience some level of it. Even common antibiotics like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can cause it in a small but real number of patients. The problem isn’t just the drop in numbers. It’s what happens when those numbers get too low. An absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 1,500 cells/μL means you’re neutropenic-your body can’t defend itself against bacteria. Hemoglobin below 13.5 g/dL in men or 12.0 g/dL in women means anemia-you’re oxygen-starved. Platelets under 150,000/μL mean you bruise easily; under 50,000/μL, you’re at risk of spontaneous bleeding. These aren’t abstract lab values. They’re life-or-death thresholds.Which Medications Cause It?

Chemotherapy is the biggest culprit. About 70 to 80% of cases come from cancer drugs. Carboplatin, for example, causes severe thrombocytopenia in 30 to 40% of patients. Fludarabine leaves 65% of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with dangerously low lymphocyte counts. But it’s not just chemo. Immunosuppressants like azathioprine, used after organ transplants, cause suppression in 5 to 10% of users. Even drugs like chloramphenicol or phenytoin can trigger it in rare cases. The timing matters too. Most suppression hits 7 to 14 days after starting treatment-the so-called “nadir.” That’s when counts are lowest. For many, it’s the most dangerous week. You feel fine one day, then wake up with a fever and no energy. That’s not just fatigue. It’s your immune system collapsing.How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no mystery here. A simple blood test-called a complete blood count, or CBC-tells the whole story. Doctors check three things: hemoglobin for red cells, ANC for white cells, and platelet count. Weekly CBCs are standard during chemotherapy. For high-risk patients, some hospitals check every 48 to 72 hours. If counts keep dropping without explanation, a bone marrow biopsy may be needed. But in most cases, the cause is clear: you’re on a drug known to suppress marrow. The key is catching it early. A platelet count of 120,000/μL might not sound bad. But if it was 250,000 last week, that’s a red flag. Tracking trends is more important than single numbers.

What Happens When Counts Get Too Low?

Low blood counts don’t just make you feel bad-they can kill you. Neutropenia leads to neutropenic fever: a temperature above 38.3°C (101°F) with no other obvious cause. That’s a medical emergency. Your body has no white cells left to fight infection. Without antibiotics within hours, sepsis can set in. Platelets under 10,000/μL mean you could bleed internally from a minor bump. Anemia under 8 g/dL leaves you breathless walking to the bathroom. Patients report feeling like they’re running on empty. One woman on Reddit described it as “walking through wet cement.” Another said he stopped seeing his grandkids because he was too weak to hold them-and scared he’d catch something from them. These aren’t just symptoms. They’re life interruptions.How Is It Treated?

Treatment depends on severity. Mild cases (grade 1-2) often just need a delay in medication or a lower dose. But severe cases (grade 3-4) demand action. For neutropenia, growth factors like filgrastim (Neupogen) or pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) are the go-to. They stimulate your bone marrow to make more white cells. Studies show they cut the duration of neutropenia by over 3 days on average. But they’re expensive-up to $6,500 out-of-pocket in the U.S. Some patients skip doses because of cost. Trilaciclib (COSELA) is newer. Approved in 2021, it’s given right before chemo to protect the bone marrow. In trials, it cut myelosuppression by 47% in small cell lung cancer patients. It’s not a cure, but it’s a shield. For anemia, transfusions are used when hemoglobin drops below 8 g/dL. For platelets, transfusions kick in below 10,000/μL or if there’s active bleeding. These aren’t long-term fixes-they’re stopgaps. If azathioprine caused the problem, switching to mycophenolate mofetil helps restore counts in 78% of transplant patients within six weeks. Sometimes, the drug itself needs to go.What About Long-Term Risks?

Growth factors aren’t harmless. Long-term use of G-CSF drugs like filgrastim has been linked to a 12.3% higher risk of osteoporosis in older adults. The FDA has black box warnings about possible stimulation of cancer cells. And while Trilaciclib is promising, it’s only approved for specific cancers. There’s also the emotional toll. A 2022 survey found 74% of cancer patients had treatment delayed because of low counts. Nearly half stopped therapy entirely. That’s not just a side effect-it’s a treatment failure. Patients don’t just lose blood counts. They lose hope.

What Can You Do?

You can’t always prevent it, but you can manage it.- Know your numbers. Ask for your CBC results after every cycle. Don’t wait for your doctor to bring it up.

- Monitor for fever. Take your temperature daily during chemo. Any fever over 38.3°C? Go to the ER. Don’t wait.

- Watch for bleeding. Unexplained bruising, nosebleeds, or blood in urine or stool? Call your oncologist immediately.

- Ask about alternatives. If you’re on azathioprine and your counts are dropping, ask if mycophenolate is an option.

- Ask about protection. If you’re on chemo, ask if Trilaciclib is appropriate for your cancer type.

- Don’t ignore cost. If G-CSF is too expensive, talk to your hospital’s financial aid office. Some drug manufacturers offer patient assistance programs.

Just had my third round of chemo last week and my platelets dropped to 98k. I didn’t realize how fast it could happen until I started bruising just from hugging my dog. I started checking my CBC every 48 hours after this - total game changer. Don’t wait for your doc to bring it up. Ask. Always.

Also, if you’re on carboplatin and your counts are tanking, ask about dose adjustments or trilaciclib. My oncologist said it’s not for everyone, but it’s worth a conversation.

Look I’ve been in this game for 17 years as an oncology nurse and let me tell you nobody talks about this enough. Bone marrow suppression isn’t a side effect it’s a fucking war zone and you need to treat it like one. Your ANC below 1500 isn’t a lab number it’s a red flag waving in a hurricane. I’ve seen people die because they waited until they were feverish to call. One day you’re fine next day you’re in septic shock and your white cells are at 200. That’s not bad luck that’s negligence. And don’t even get me started on the cost of Neulasta. People skip doses because they can’t afford it and then wonder why they’re back in the hospital. The system is broken but your body doesn’t care about insurance. Know your numbers or get left behind.

Trilaciclib isn’t magic but it’s the closest thing we’ve got to armor before the battle. If you’re eligible get it. If your doc won’t prescribe it find another doc. Your life is worth more than their paperwork.

I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My mom went through this last year and I didn’t understand why she was so tired all the time. I thought it was just the chemo. Turns out her hemoglobin was at 7.8 and no one told us how dangerous that was. We started checking her temps daily and caught a fever before it turned into something worse. I’m so glad you mentioned the emotional toll too. It’s not just physical - it’s like losing pieces of yourself every week.

Wow. Another one of those ‘you’re not doing enough’ guilt-trip articles. Let me guess - you’re pushing trilaciclib because Big Pharma paid you? I’ve seen too many patients get hit with $6000 shots that barely help. The real problem is we keep treating cancer like a math problem instead of a human one. You don’t fix bone marrow suppression by throwing money at it. You fix it by stopping the damn drugs that cause it in the first place. Why not try immunotherapy or diet or acupuncture? Oh right - those don’t make billions. But hey, at least your lab reports look pretty.

Thank you for sharing this. I’m a nurse in a rural clinic and I see so many patients who don’t have access to regular CBCs or financial aid programs. I wish more people knew how simple it is to ask for their numbers - just say ‘Can I see my CBC results?’ after every infusion. It takes 30 seconds. And if you’re on azathioprine and your counts are dropping? Mycophenolate is a real alternative. I’ve seen people bounce back in weeks. You’re not alone. Talk to someone. Even if it’s just a nurse. We’re here.

Okay but have you considered that maybe the real issue is that Americans are too lazy to eat real food? My grandma in the 50s took penicillin for a sinus infection and never had a drop in her blood counts. Now everyone’s on 12 different meds and freaks out because their platelets are 140k. It’s not the drugs - it’s the sugar, the processed everything, the lack of sunlight. Fix your lifestyle before you ask for a $6000 shot. Also, why are we giving cancer patients growth factors? Isn’t that like pouring gasoline on a fire?

YESSSSS this is the info I needed!! 🙌✨ Bone marrow suppression is the silent assassin and nobody talks about it! I’m a CLL survivor and fludarabine nearly took me out - ANC dropped to 180 and I had a 102.5 fever at 3am. Got to the ER in 20 mins. They gave me IV antibiotics and filgrastim stat. Trilaciclib? I didn’t have access back then but I’m screaming for it now for my cousin on SCLC. Pro tip: if you’re on chemo and feel ‘off’ - even if you don’t have a fever - GET LABS. Don’t wait. Your marrow is whispering. Listen. 💪🩸 #BoneMarrowWarrior #KnowYourNumbers

I’ve been on azathioprine for 8 years after my transplant. My counts dropped hard last winter - hemoglobin hit 8.1. I cried for three days. Then I asked for mycophenolate. Switched in two weeks. My numbers are back to normal. No transfusions. No growth factors. Just a different pill. I’m not saying chemo is bad - I’m saying your body is smarter than your prescription pad. Speak up. Ask for alternatives. You’re not being difficult. You’re being alive.