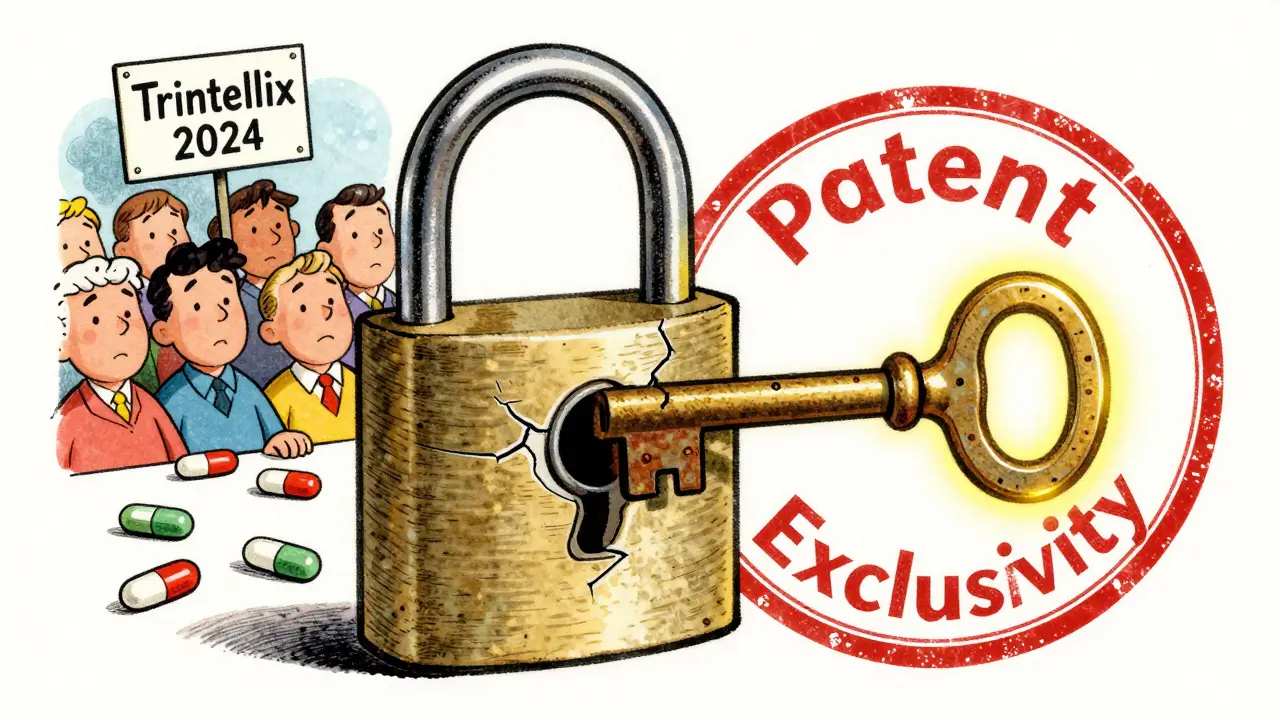

When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just have a patent. It has patent exclusivity and market exclusivity-two separate shields that keep generics off the shelf. Many people think they’re the same thing. They’re not. And understanding the difference could explain why some drugs stay expensive for years-even after their patent expires.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Right to Exclude

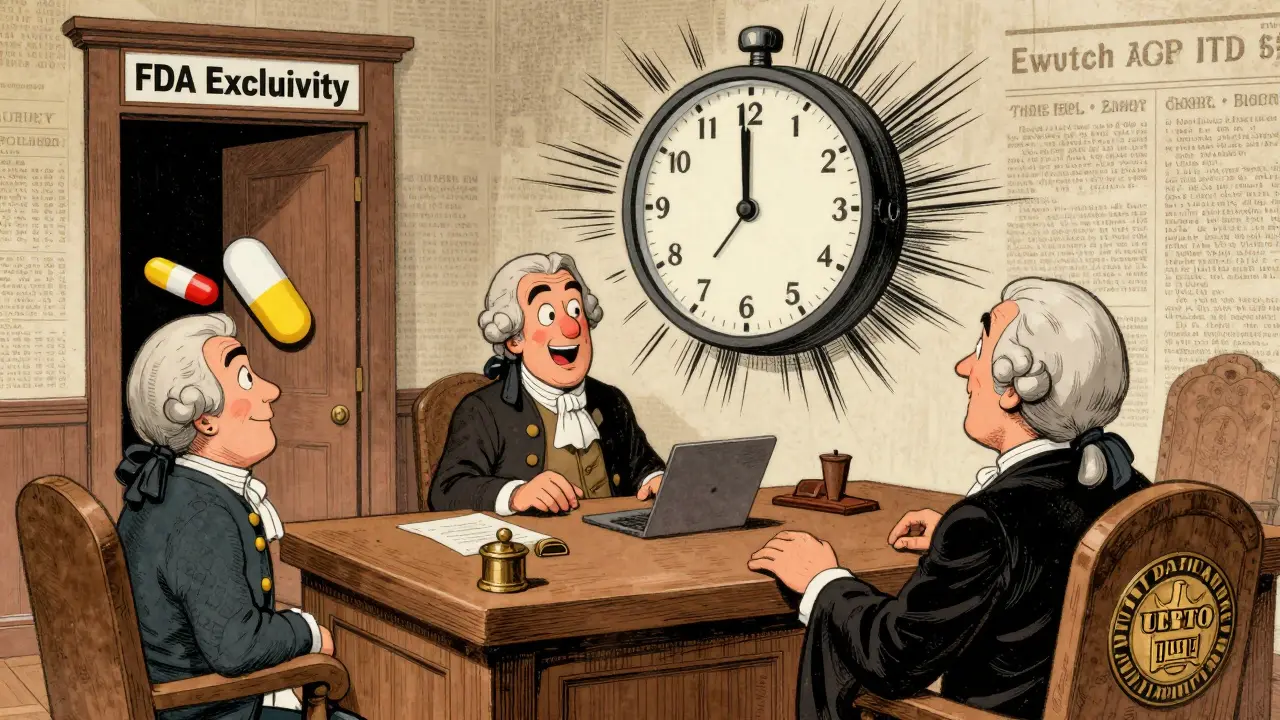

A patent is a legal tool granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) a federal agency responsible for granting patents and trademarks in the U.S.. It gives the drugmaker the right to stop others from making, selling, or using their invention. For pharmaceuticals, this usually means the exact chemical structure, how it’s made, or how it’s used to treat a disease.

By law, a patent lasts 20 years from the day it’s filed. But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years just to get approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the U.S. government agency that approves drugs for safety and effectiveness.. That means by the time the drug hits shelves, you might only have 5 to 10 years of real market protection left.

That’s why companies can ask for a Patent Term Extension (PTE) a legal adjustment to extend patent life to make up for time lost during FDA review.. The law allows up to 5 extra years, but the total time after FDA approval can’t go beyond 14 years. So if a drug got approved in year 12 of its patent, it could get 2 more years of protection.

But patents aren’t automatic blockers. If a generic company thinks your patent is weak or invalid, they can challenge it in court. That’s why many drugmakers file dozens of secondary patents-on pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods-to keep generics out longer. In fact, 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary, not the core chemical patent.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Silent Gatekeeper

Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s a separate protection granted by the FDA when a drug is approved. The FDA won’t even look at a generic version until this period ends-even if the patent has expired.

There are several types, and they vary by drug:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. During this time, the FDA can’t accept any generic application that relies on the original drug’s data. This is the most common type.

- Orphan drug exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients). Even if there’s no patent, this kicks in automatically.

- Pediatric exclusivity: 6 months added to existing exclusivity or patent time. Companies get this by doing extra studies on how the drug affects children.

- Biologics exclusivity: 12 years. For complex drugs made from living cells, like insulin or cancer treatments. This was created by the 2009 BPCIA law.

- 180-day exclusivity: Given to the first generic company that successfully challenges a patent. This can be worth hundreds of millions in revenue.

Here’s the kicker: market exclusivity can exist without a patent. In 2010, a company got 10 years of exclusivity for colchicine a centuries-old drug used for gout, originally sold for pennies per tablet.. The FDA approved it as a new use-despite it being an ancient remedy. The price jumped from 10 cents to $5 per tablet. No patent. Just exclusivity.

Why Both Exist: The Hatch-Waxman Balance

The whole system was designed in 1984 by the Hatch-Waxman Act a landmark U.S. law that balanced innovation incentives with generic competition.. Before that, drugmakers had no way to recover R&D costs, and generics couldn’t enter until patents expired-delaying affordable options.

Hatch-Waxman let generics file applications without repeating expensive clinical trials. But in return, innovators got time to recoup investment through patents and exclusivity. It was meant to be a trade-off. Today, it’s become a two-key lock: you need both to fully block competition.

According to FDA data from 2021:

- 27.8% of branded drugs have both patent and exclusivity

- 38.4% have only patents

- 5.2% have only exclusivity

- 28.6% have neither

That 5.2%? Those are drugs with no patent protection at all-but still no generics because of exclusivity. The FDA’s own data shows 78% of these drugs still had zero generic competition during their exclusivity period.

Real-World Impact: Who Gets Hurt?

When exclusivity and patents overlap, it creates confusion. Take Trintellix an antidepressant approved in 2016 with 3 years of regulatory exclusivity.. Its patent expired in 2023-but generics still couldn’t launch until 2024 because of exclusivity. Teva, the generic maker, lost an estimated $320 million in delayed sales.

Smaller companies often don’t know the difference. A 2022 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) a trade group representing biotech firms. found 43% of small firms mistakenly thought patent expiration meant generics could enter. They didn’t file for exclusivity-and lost out on years of protection.

And it’s expensive to get it right. Preparing exclusivity claims takes 120 to 150 hours of regulatory work per drug. The average medium-sized company spends $2.5 million a year just managing these filings.

Meanwhile, the cost to develop a new drug is $2.3 billion, with over $700 million spent on clinical trials alone. That’s why companies fight so hard to stretch exclusivity. The average branded drug makes 65% of its lifetime revenue in the first year after launch.

What’s Changing? The Future of Drug Protection

The system is under pressure. In 2023, the FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard a public tool that tracks all active exclusivity periods in real time.. Now, anyone can see when a drug’s exclusivity ends. That’s great for generics-but not so great for innovators.

The PREVAIL Act a proposed U.S. law introduced in 2023 to reform biologics exclusivity. wants to cut biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. If passed, it could speed up access to cheaper biosimilars.

And globally, the debate is heating up. The WTO’s 2022 decision to waive patent rules for COVID-19 vaccines has sparked talks about applying similar rules to cancer drugs, diabetes meds, and more. If countries start ignoring exclusivity, the U.S. system could become an outlier.

By 2027, analysts at McKinsey a global consulting firm that tracks pharmaceutical trends. predict regulatory exclusivity will account for 52% of total market protection time-up from 41% in 2020. Patents are getting weaker. Exclusivity is getting stronger.

Bottom Line: Two Keys, One Lock

Patent exclusivity is about invention. Market exclusivity is about approval. One is enforced by courts. The other by the FDA. You can have one without the other. And when both are in place, generics stay out for years-even if the patent is dead.

If you’re a patient, it means higher prices. If you’re a generic maker, it means legal battles and delays. If you’re a drugmaker, it’s your lifeline. The system was built to encourage innovation. But today, it often feels like a loophole factory.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. Market exclusivity is granted by the FDA based on the drug’s approval, not its patent status. For example, orphan drugs or reformulated versions of old drugs can get exclusivity even if they aren’t patented. The 2010 colchicine case is a well-known example-no patent, but 10 years of exclusivity.

What happens when a patent expires but exclusivity is still active?

Generic manufacturers still can’t launch. The FDA is legally blocked from approving any competing product until the exclusivity period ends-even if the patent has expired. This is why some drugs stay brand-only for years after their patent is gone.

Do all drugs get market exclusivity?

No. Only certain types qualify. New Chemical Entities get 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7. Biologics get 12. Pediatric studies add 6 months. But if a drug is a simple reformulation of an existing one, or if the company doesn’t properly file for exclusivity, they may get none.

How long does it take the FDA to decide on exclusivity?

The FDA typically makes a decision within 45 days after drug approval. But 12% of applications are incomplete or incorrect, which delays the process. Companies that miss deadlines or submit incomplete data risk losing exclusivity entirely.

Why do some companies file so many secondary patents?

Because once the main patent expires, secondary patents (on coatings, dosing, delivery systems) can still block generics. Since patents are easier to challenge than exclusivity, companies pile them on to delay competition. About 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary-not the original chemical patent.

What to Watch Next

If you’re tracking drug prices or generic access, keep an eye on the FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard. It’s now public, and generic companies are using it to time their launches. Also, watch for the PREVAIL Act. If it passes, it could reshape how biologics are protected. And remember: when a drug’s patent expires, it’s not necessarily time for generics to arrive. The real gatekeeper? The FDA’s clock-not the patent office’s.