For years, parents were told to keep peanuts away from babies until they were at least two or three years old. It seemed like the safest choice-after all, peanut allergies can be deadly. But what if that advice was wrong? And what if waiting actually made the problem worse?

Here’s the truth: delaying peanut introduction didn’t protect kids. It helped cause the explosion in peanut allergies we saw in the 1990s and 2000s. Between 1997 and 2010, the rate of peanut allergy in U.S. children more than tripled-from 0.4% to 2.0%. By 2015, nearly one in 50 kids had a peanut allergy. That’s 200,000 emergency room visits every year in the U.S. alone.

Then came the LEAP study. Published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2015, it turned everything upside down. Researchers followed 640 high-risk infants-those with severe eczema or egg allergy-and gave half of them peanut-containing foods regularly from 4 to 11 months old. The other half avoided peanuts completely. By age five, the group that ate peanut had an 86% lower rate of peanut allergy. That wasn’t a small change. It was a revolution.

What the Guidelines Say Now

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) responded fast. In January 2017, they released new guidelines, backed by 26 major medical groups including the American Academy of Pediatrics. These aren’t suggestions-they’re science-backed rules for how to prevent peanut allergy before it starts.

The approach is simple: it depends on your baby’s risk level.

- High-risk infants (severe eczema, egg allergy): Start peanut between 4 and 6 months, but only after seeing a doctor. They may need allergy testing first. If the test is negative, give 2 grams of peanut protein-about 2 teaspoons of smooth peanut butter-three times a week.

- Moderate-risk infants (mild to moderate eczema): Start around 6 months, at home. No testing needed. Just mix peanut butter into their cereal or puree.

- Low-risk infants (no eczema or food allergies): Introduce peanut anytime after starting solids, usually around 6 months. No special steps needed.

It’s not about waiting. It’s about acting early. The window for prevention is narrow. Studies show the biggest benefit comes when peanut is introduced before 6 months. One 2023 analysis of the LEAP and EAT studies found that babies who ate peanut before 6 months had up to a 100% reduction in peanut allergy risk-if they stuck to the plan.

How to Introduce Peanut Safely

You don’t hand a baby a handful of peanuts. That’s a choking hazard. You don’t give them peanut butter straight from the jar-it’s too thick and sticky. Safe introduction means smooth, thin, and easy to swallow.

Here’s how to do it:

- Use smooth peanut butter-no chunks, no crunchy.

- Mix 2 teaspoons (about 10 grams) of peanut butter with 2-3 tablespoons of warm water, breast milk, or formula. Stir until it’s a runny paste.

- Or mix it into apple sauce, mashed banana, or infant cereal.

- For the first time, give a small taste-about 1/4 teaspoon-on the tip of a spoon. Wait 10 minutes. Watch for swelling, hives, vomiting, or trouble breathing.

- If there’s no reaction, give the rest over the next hour.

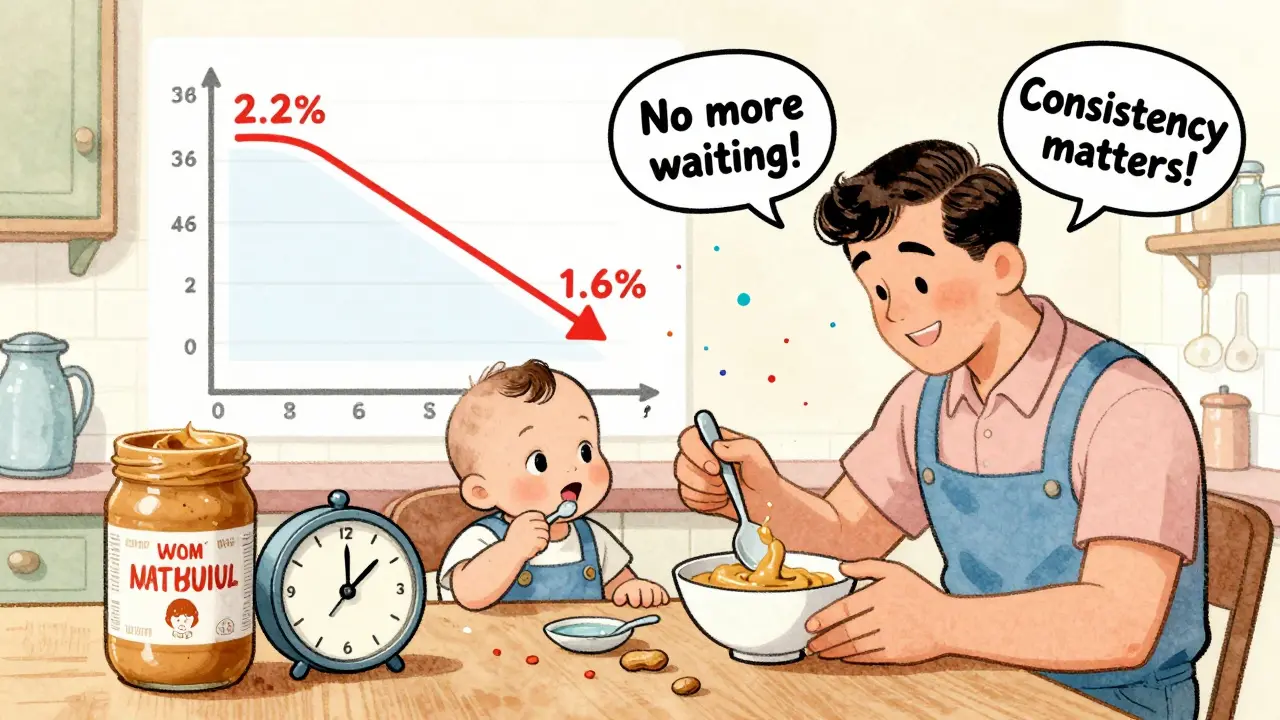

- Then keep giving peanut three times a week. Consistency matters more than how much you give at once.

Some parents use products like Bamba (a puffed corn snack with peanut), which dissolves easily and was used in the LEAP study. Others use specially designed infant peanut powders or pouches now sold in stores. But plain smooth peanut butter works just as well-and costs less.

For high-risk babies, the first dose should be given under medical supervision. That’s not because peanut is dangerous-it’s because we need to be ready if something happens. Most reactions are mild. But if your baby has severe eczema or egg allergy, a doctor’s office is the safest place to start.

What About Oral Immunotherapy (OIT)?

Some people confuse prevention with treatment. Early introduction is about preventing allergy from forming. Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) is about treating an allergy that’s already there.

OIT involves giving tiny, increasing doses of peanut protein daily under medical supervision. The goal isn’t to cure the allergy-it’s to build tolerance so a small accidental exposure won’t cause a life-threatening reaction. It’s not for babies. It’s for kids and adults who already have a confirmed peanut allergy.

Studies show OIT works: after a year, most patients can tolerate the equivalent of 1-2 peanuts. But it’s not a cure. Stopping the daily dose often brings the allergy back. Side effects like stomach pain, vomiting, or itchy mouth are common. It requires months of commitment, frequent doctor visits, and constant vigilance.

That’s why prevention is better. Preventing peanut allergy in the first place avoids the need for lifelong daily dosing, anxiety, and risk. The LEAP study showed that the protection from early exposure lasted-even after kids stopped eating peanut for a full year. That suggests true tolerance, not just temporary desensitization.

Why Isn’t Everyone Doing It?

Even with strong guidelines, most parents aren’t following them. A 2022 study found only 38.7% of high-risk infants got peanut introduced early. Why?

- Parents are scared. One survey showed 62% of parents worried about a reaction during the first feeding.

- Doctors aren’t always clear. Only 54% of pediatricians in a 2023 survey could correctly describe the NIAID guidelines.

- Confusion about what’s safe. Many still think peanut butter is too thick or that whole peanuts are okay.

- Disparities in access. Black and Hispanic infants are 22% less likely to get early peanut exposure than white infants, contributing to ongoing differences in allergy rates.

And then there’s the myth that breastfeeding or avoiding peanuts during pregnancy helps. Research shows it doesn’t. Cochrane reviews found no benefit from probiotics, vitamin D, or maternal diet changes. The only proven method is giving peanut to the baby-early and often.

What’s Changed Since 2017?

The results are in. Since the guidelines rolled out, peanut allergy rates have dropped. In the U.S., the rate fell from 2.2% in 2015 to 1.6% in 2023. That’s about 300,000 fewer children with peanut allergy.

And the drop isn’t random. The biggest declines happened in high-risk groups:

- 85% reduction in children with mild eczema

- 87% reduction in children with moderate eczema

- 67% reduction in children with severe eczema

That’s not luck. That’s science working.

Industry has responded too. Peanut-based infant foods-like spoonable pouches and powdered mixes-have grown 27% a year since 2018. The U.S. peanut allergy market is now worth $1.8 billion, but more of that money is going into prevention than treatment.

Future research is even more promising. The PRESTO trial, funded by the NIAID with $35 million a year, is testing whether giving peanut even earlier-before 4 months-could help even more. Results are expected in 2026.

And now, experts are looking at introducing multiple allergens at once. The EAT study showed that adding egg, milk, and sesame along with peanut didn’t increase risk-it lowered overall food allergy rates. The future may not be just about peanut. It’s about teaching the immune system to accept many foods early.

What Parents Should Do Today

If you’re expecting or have a baby under 12 months, here’s what to do:

- Check your baby’s risk level. Do they have severe eczema? Egg allergy? Then talk to your pediatrician before 4 months.

- If they have mild eczema, start peanut at 6 months. No test needed.

- If they have no eczema or allergies, just add peanut when you start solids-no rush, no fear.

- Use smooth peanut butter. Dilute it. Don’t use whole peanuts or crunchy peanut butter.

- Give peanut three times a week. Keep going. Don’t stop after one try.

This isn’t a one-time decision. It’s a habit. Like tummy time or brushing teeth. Do it consistently, and you’re not just feeding your baby-you’re protecting them.

There’s no magic pill. No supplement. No special diet. Just peanut-and the courage to give it early.

Can I give my baby peanut butter straight from the jar?

No. Full-strength peanut butter is too thick and sticky for babies under 12 months. It’s a choking hazard. Always dilute smooth peanut butter with water, breast milk, or formula to make a runny paste. You can also mix it into cereal or pureed fruits.

Is peanut allergy testing required before introducing peanut?

Only for high-risk infants-those with severe eczema or egg allergy. For these babies, a doctor may recommend a skin prick test or blood test before the first peanut exposure. If the test is negative, they can start peanut at home. If it’s positive, an allergist will guide next steps. For moderate or low-risk babies, testing isn’t needed.

What if my baby has a reaction to peanut?

Mild reactions like a rash or lip swelling should be monitored. Stop peanut and contact your pediatrician. If your baby has trouble breathing, swelling of the throat, vomiting, or becomes limp, call emergency services immediately. For high-risk babies, the first peanut dose should be given under medical supervision to avoid delays in treatment.

Does introducing peanut early help if my child already has a peanut allergy?

No. Early introduction is only for preventing allergy in babies who don’t have it yet. If your child already has a confirmed peanut allergy, you should avoid peanut entirely and work with an allergist. Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) is the treatment option for existing allergies, but it’s not the same as prevention.

Are peanut allergy rates really going down?

Yes. Since the 2017 guidelines, peanut allergy rates in U.S. children have dropped from 2.2% to 1.6% by 2023. That’s about 300,000 fewer children affected. The biggest drop is in high-risk groups-children with eczema-who saw reductions of 67% to 87% depending on severity. The trend is clear: early introduction works.

Just introduced peanut butter to my 5-month-old last week-mixed it into her oatmeal like the guide said. No reaction, no drama. She loved it. I’m so glad we didn’t listen to the old ‘wait until 3’ nonsense. My cousin’s kid had a full-blown anaphylaxis at 2 because they waited. This stuff saves lives.

Let me be clear: this is not ‘science.’ This is corporate manipulation disguised as public health policy. The peanut industry lobbied for this. They’ve been pushing infant peanut products for years. And now, suddenly, we’re told to feed babies something that used to be considered dangerous? Coincidence? I don’t think so.

There’s no long-term data on neurodevelopmental effects. No studies on gut microbiome disruption. And yet, we’re being told to rush this in? It’s reckless. And the fact that pediatricians are pushing it without skepticism? That’s the real crisis.

My kid ate peanut at 4 months. No allergy. Now he’s 3 and eats peanut butter straight out of the jar. I’m not a hero. I just followed the data. The fear was always the problem.

What if the real problem isn’t when we introduce peanuts-but that we’ve been poisoning our kids with processed food since birth? We’re treating symptoms while ignoring the root cause: industrial diets, glyphosate, formula over breast milk. Early peanut exposure is a band-aid on a bullet wound.

And yet, we’re told to celebrate this as a breakthrough. How convenient. The same system that sold us formula, then processed baby food, now sells us peanut pouches. Who profits? Always the same people.

So let me get this straight-now we’re supposed to trust doctors who spent 20 years telling us to avoid peanuts entirely? And now, overnight, they flip the script and expect us to just… believe them? What’s next? ‘Oh, by the way, vaccines cause autism, but only if you give them after 18 months.’

This is why people don’t trust medicine anymore. One day it’s ‘dangerous,’ the next it’s ‘life-saving.’ Who’s really in charge here?

My daughter had eczema. We did the skin test. Positive. We were told to wait. We didn’t. We gave her peanut butter at 5 months. She had a tiny rash. We called the pediatrician. They said ‘it’s fine, keep going.’ She’s 2 now. No allergy. I’m not saying this to brag-I’m saying it because people need to know: the fear is worse than the reaction.

And if your doctor doesn’t know the guidelines? Find a new one. This isn’t optional. It’s basic.

I’m so grateful for this info. I almost didn’t introduce peanut because I was terrified. But reading the LEAP study changed everything. Now I give my 7-month-old peanut 3x a week-mixed into mashed sweet potato. She smiles every time. 😊 I wish I’d known this sooner. So many parents are scared, but the science is so clear. We can protect our kids. We just have to act.

My mom kept saying, ‘I never gave my kids peanut until they were 5, and look at them-healthy!’ Yeah, but you also didn’t have 1 in 50 kids with allergies back then. The world changed. The data changed. We have to change with it.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being informed. And honestly? If you’re still scared, start with Bamba. It’s like a crunchy cheerio with peanut. Way safer than peanut butter.

Why are we letting the government tell us how to feed our kids? This is socialism disguised as medicine. Next they’ll ban sugar, then carbs, then milk. Who gave them the right?

So you’re telling me the entire medical establishment was wrong for 20 years, and now we’re supposed to trust them again? That’s not science. That’s institutional arrogance. And now they’ve created a $1.8 billion industry around infant peanut products? Who funded the LEAP study? Who profits from the ‘safe’ peanut powders? The same companies that sold us formula, then processed baby food, then organic snacks.

This isn’t prevention. It’s monetized fear. And you’re falling for it.