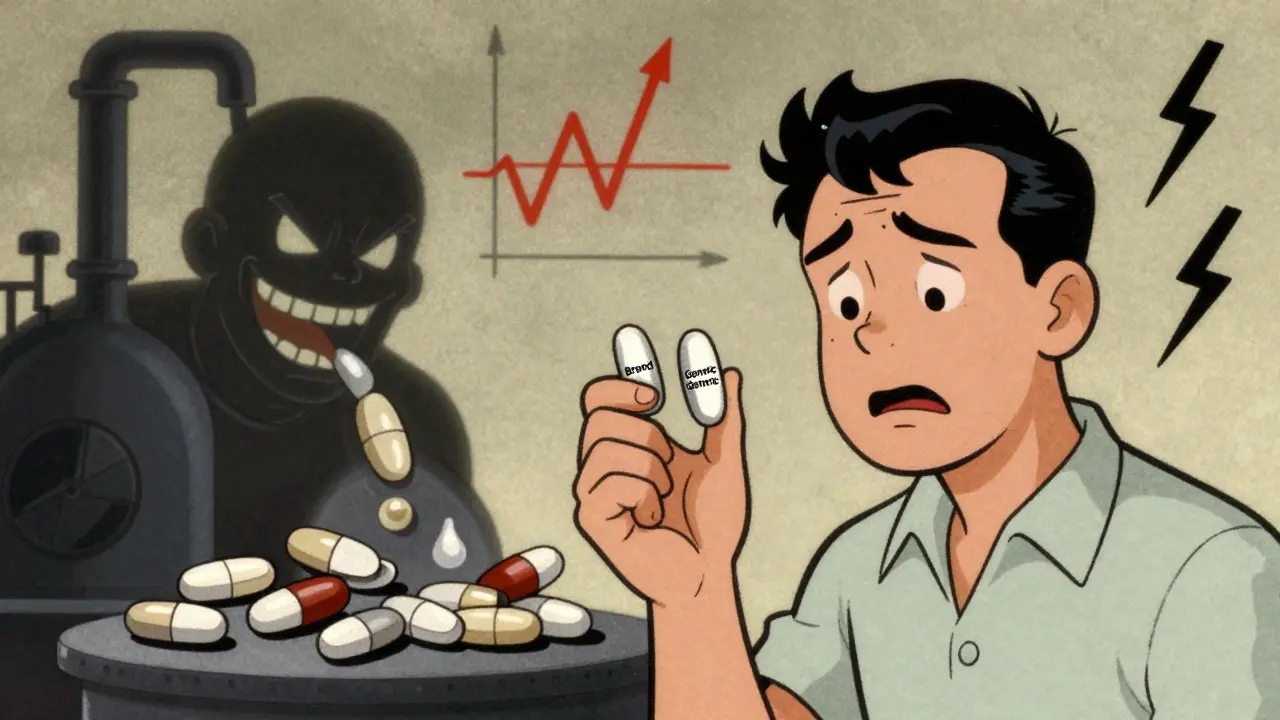

It’s supposed to be the same drug. Same active ingredient. Same dose. Cheaper. But for some patients, the generic version just doesn’t work. Their seizures return. Their blood pressure spikes. Their cancer progresses. And they’re left wondering: Why did the generic fail?

What Happens When a Generic Drug Doesn’t Work?

Generic drugs are meant to be exact copies of brand-name medications. The FDA requires them to contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and to be absorbed into the body at a similar rate. But here’s the catch: that similarity isn’t perfect. The legal standard allows a generic to be absorbed anywhere between 80% and 125% as fast as the brand-name version. That’s a 45% window. For most drugs, it’s fine. For others, it’s dangerous.Take warfarin, a blood thinner. Too little, and you get a clot. Too much, and you bleed internally. A patient stable on brand-name Coumadin might switch to a generic and suddenly have a stroke-or a dangerous bleed. There’s no warning. No sudden rash. Just a quiet, deadly shift in how the drug behaves inside the body.

This isn’t rare. In 2013, the FDA pulled Budeprion XL, a generic version of Wellbutrin, after hundreds of patients reported severe side effects: anxiety, dizziness, even suicidal thoughts. The problem? The inactive ingredients changed how the tablet broke down. The active drug released too fast-or too slow. The pill looked the same. The label said the same thing. But inside, it was different.

Why Do Generic Drugs Fail? It’s Not Just the Active Ingredient

The active ingredient is only half the story. The rest-fillers, coatings, binders-controls how the drug dissolves. If the coating is too thick, the pill won’t break down in the gut. If the binder is too hard, the drug gets trapped. If the granules aren’t mixed evenly, some pills have twice the dose of others.One study found that only 4 out of 12 generic versions of a popular ADHD medication dissolved at the same rate as the brand. One generic dissolved three times faster. That’s not a small difference. That’s the difference between a child staying focused all day and having a meltdown by lunchtime.

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like digoxin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, or tacrolimus-the margin for error is razor-thin. The FDA requires stricter testing for these, but even then, problems slip through. In one investigation, multiple sclerosis patients on generics with 91% to 72% of the labeled dose had relapses. Those on generics with 97% to 103% stayed stable. The difference? A few percentage points in the pill’s content.

Manufacturing Problems Are Common-and Hidden

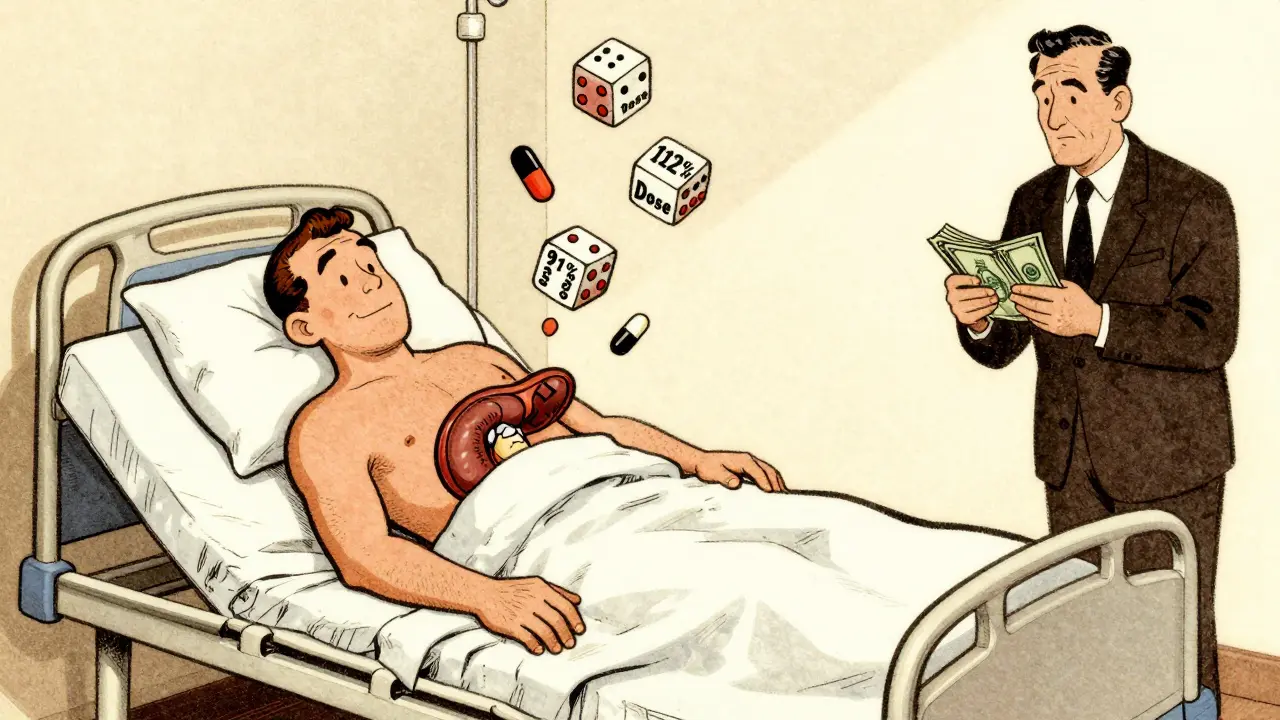

Thirty-one percent of all deficiencies in generic drug applications come from manufacturing issues. That’s more than one in three. Drug substance problems? Nine percent. Drug product problems? Twenty-seven percent. That includes unstable formulations, poor dissolution, and inconsistent active ingredient distribution.Investigators found pills from the same blister pack containing wildly different amounts of active drug. One tablet had 88% of the labeled dose. Another in the same pack had 112%. That’s not a typo. That’s a quality control failure. And it’s happening in factories across the globe.

Some generics are made in countries with weak oversight. A chemotherapy drug meant to treat leukemia was found to contain only 65% of the active ingredient. Giving that to a patient isn’t treatment. It’s a death sentence.

In 2024, Glenmark recalled nearly 47 million doses of potassium chloride because the tablets didn’t dissolve. Patients with low potassium levels were at risk of heart arrhythmias. The pills looked fine. They tasted fine. But inside, they were useless.

Who’s Responsible When a Generic Fails?

It’s not always the manufacturer. The supply chain is long. A drug might be made in India, shipped to a U.S. warehouse, repackaged by a middleman, then sold through a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). Each step adds cost-and opportunity for error.Pharmacies often switch generics without telling patients. A doctor prescribes one brand. The pharmacy fills it with another-cheaper, approved, but different. The patient doesn’t know. The doctor doesn’t know. And when the patient gets worse, everyone assumes it’s the disease.

Experts warn that the system is built to prioritize cost over consistency. PBMs profit from switching to the cheapest generic-even if it’s less reliable. Patients pay with their health.

Which Drugs Are Most at Risk?

Not all generics are created equal. Some categories carry higher risk:- Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs: Warfarin, digoxin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, lithium, theophylline.

- Extended-release formulations: Concerta, Wellbutrin XL, OxyContin generics.

- Cancer treatments: Methotrexate, doxorubicin, paclitaxel.

- Anticonvulsants: Carbamazepine, valproic acid.

- Immunosuppressants: Used after transplants.

These drugs demand precision. A 10% variation in dose can mean the difference between control and crisis.

What Should Patients Do?

If you’re on a generic drug and notice something’s off-new side effects, reduced effectiveness, unexpected symptoms-don’t assume it’s your body changing. Ask questions.- Check the label. Is the generic name the same as the one you’ve been taking?

- Ask your pharmacist: Is this the same generic I’ve used before?

- Ask your doctor: Could this be a generic failure?

- Keep a symptom journal. Note when you started the new generic and what changed.

- Request the brand-name version if your condition is critical. Many insurers will approve it if you document therapeutic failure.

Don’t be afraid to push back. Your life may depend on it.

The Bigger Picture: A Broken System

The generic drug market is worth over $400 billion. But quality control is patchy. Regulatory oversight is uneven. Transparency is minimal. And patients are caught in the middle.The FDA’s approval process was designed for efficiency, not perfection. It works for most drugs. But for the ones that need precision? It’s not enough.

Experts call it a systemic failure. When patients on generics for heart transplants start having rejection symptoms because the drug wasn’t absorbed properly, it’s not bad luck. It’s a breakdown in safety monitoring.

Until manufacturers are held to consistent global standards, until pharmacies are required to disclose every switch, and until doctors are trained to recognize generic failure as a real possibility-patients will keep paying the price.

Generic drugs save money. That’s good. But not if they cost lives.

Generic drugs are a scam. Period.

I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years. Switched generics last year and started feeling like a zombie at 3 p.m. - no energy, brain fog, cold all the time. Took me months to figure out it wasn’t me. It was the pill. Now I fight my insurer for the brand. Worth every call, every email. Your body remembers what works. Trust it.

Let me tell you about my cousin - brilliant woman, 42, on tacrolimus after her kidney transplant. They switched her to a generic without a word. Three weeks later, her creatinine spiked. She ended up back in the hospital. The docs said it was "fluctuations." Fluctuations?! The pill was barely dissolving. They tested the tablets - one had 89% of the labeled dose, the next one in the same bottle had 114%. That’s not a variation. That’s a lottery. And she’s not a number - she’s a mother who almost died because someone in a boardroom decided to save $0.12 per pill. This isn’t healthcare. It’s corporate roulette.

Y’all need to STOP blaming the FDA. The real villains are the PBMs. They don’t care if you live or die - they care if the generic is 3 cents cheaper than the last one. And pharmacies? They’re just the middlemen who don’t even know what’s in the bottle half the time. I work in a pharmacy - we get 12 different versions of the same generic. We just grab the one with the highest rebate. No one tells the patient. No one checks if it’s the same one they were on. It’s insane. We’re literally playing Russian roulette with people’s lives.

My mom’s on digoxin - she’s 78, heart failure. She switched generics in January. Started getting dizzy, nauseous, her pulse got erratic. We thought it was aging. Then we checked the bottle - different maker. We called the pharmacist. They said, "Oh, we switched to the cheaper one." We demanded the old one back. They said no. We called the doctor. Doctor called the insurer. Took three weeks. She’s stable now. But it took a miracle. Don’t let this happen to you. Keep a log. Demand the same maker. Write down the name on the pill bottle. It’s your life.

They pulled Budeprion XL because people were having panic attacks? That’s not a coincidence. That’s a crime. And now? They’re still selling other generics with the same flawed dissolution profile - just under a different name. The FDA doesn’t test every batch. They test one. One. And if it passes? Congrats, you’ve got a 45% window of potential disaster. I’ve seen patients on carbamazepine go from seizure-free to convulsing because the generic dissolved too fast. It’s not placebo. It’s pharmacology gone rogue. And nobody’s auditing the factories in India where most of this stuff is made. Shameful.

I come from India - I’ve worked in pharma labs here. We make generics for the world. Yes, some factories cut corners. But many are excellent. The problem isn’t the country - it’s the system. The U.S. buys the cheapest, then blames the maker. We need transparency - batch numbers, dissolution data, factory audits published. Not secrecy. Not profit. Safety. We can fix this. But only if we stop pointing fingers and start demanding better.

Ah, yes - the great capitalist paradox: efficiency versus existential integrity. The commodification of pharmacology reduces the human organism to a mere variable in a cost-benefit algorithm. When the body becomes a ledger, and the pill a commodity, we have not advanced - we have regressed into a post-ethical dystopia where the soul is priced at $0.07 per tablet. The FDA, in its bureaucratic inertia, has become the priest of this secular religion - consecrating mediocrity as virtue. And we, the faithful, swallow it - literally - without a second thought.

my dr switched me to a generic for my anxiety med and i felt like i was drowning in slow motion. i cried for 3 days straight. i thought i was going crazy. turns out the pill was different. now i beg for the brand. no shame. my mental health > their profit. ps: i spelled 'generic' wrong in my notes. oops.

The data is clear. Variability exists. Regulatory oversight is insufficient. Patient advocacy is critical. Systemic reform is overdue. Thank you for raising this issue.

My nephew is autistic and on methylphenidate. Brand-name worked. Generic? He went from calm to screaming in the car. School called. Teacher thought he was having a meltdown. We didn’t know it was the pill. We thought he was regressing. Turned out the generic dissolved in 15 minutes - not 12 hours. He got a massive spike, then crashed by noon. We switched back. Now I check the pill bottle every time. If it looks different? I call the pharmacy. No excuses. Kids deserve precision. Not guesswork.

I just want everyone to be safe. If your medicine feels off, trust that feeling. Talk to someone. Don’t suffer in silence. We all deserve to feel okay.