Most people don’t realize that tuberculosis can live inside them for years without causing any harm. It’s not always the coughing, fever, and weight loss you see in movies. Sometimes, it’s silent. That’s the difference between latent TB and active TB-and why knowing the difference can save lives.

What Is Latent TB Infection?

Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) means the bacteria that cause TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, are in your body-but they’re asleep. Your immune system has locked them down in tiny clusters called granulomas, usually in your lungs. You feel fine. You don’t cough. You can’t spread it to anyone. And your chest X-ray looks normal.

This isn’t rare. About one-quarter of the world’s population has latent TB. In the U.S., it’s most common among people born in countries where TB is widespread, people who’ve lived in crowded places like prisons or homeless shelters, and healthcare workers exposed over time. A positive skin test (TST) or blood test (IGRA) is the only way to know you have it. No symptoms. No fever. No weight loss. Just a positive test and a quiet threat.

The scary part? About 5-10% of people with latent TB will eventually develop active disease. That risk jumps to nearly 50% if you’re living with untreated HIV. Diabetes, kidney failure, or taking immunosuppressants like steroids or biologics for autoimmune diseases also increases your chances. The bacteria aren’t gone-they’re just waiting for your defenses to weaken.

What Turns Latent TB Into Active Disease?

Active TB happens when the bacteria wake up, multiply, and start destroying tissue. This usually occurs within two years after infection (called primary TB), but it can also happen decades later. Your immune system can’t keep up anymore. The granulomas break down. The bacteria spread through your lungs or even to your spine, brain, or kidneys.

Signs of active TB don’t come on suddenly. They creep in over weeks: a cough that won’t quit (lasting more than three weeks), night sweats so heavy you need to change your sheets, unexplained weight loss, constant fatigue, and a low fever that doesn’t go away. Some people cough up blood. Others feel chest pain when they breathe or laugh. These aren’t just cold symptoms-they’re warning signs that your body is fighting a serious infection.

Diagnosis requires more than a blood test. You’ll need a chest X-ray, which often shows spots or cavities in the lungs. And you’ll need sputum tests: samples of your coughed-up mucus checked under a microscope or tested with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to find TB DNA. A culture-growing the bacteria in a lab-takes weeks but confirms the diagnosis and checks for drug resistance.

How Is Latent TB Treated?

Treating latent TB isn’t about curing symptoms-it’s about preventing disease before it starts. The goal is to kill the dormant bacteria before they wake up. The standard treatment has been nine months of daily isoniazid (INH). It’s cheap, effective, and used for decades. But sticking with it for that long is hard. Side effects like nausea, liver stress, or tingling in the hands and feet make people quit.

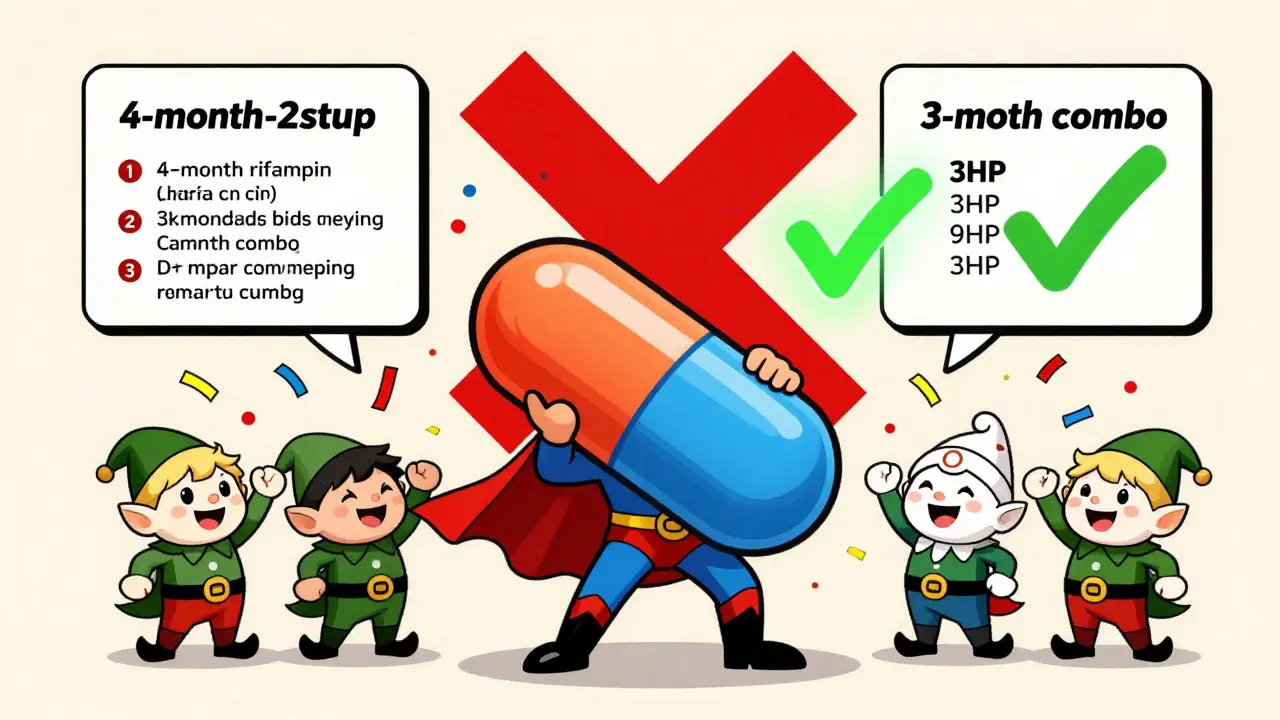

Thankfully, there are better options now. The CDC and WHO recommend shorter regimens to improve completion rates:

- 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine (3HP)

- 4 months of daily rifampin

- 3 months of daily isoniazid and rifampin

These regimens are just as effective as nine months of isoniazid-but much easier to finish. A study showed that 89% of people completed the 3HP regimen compared to only 63% on the nine-month isoniazid plan. That’s a game-changer for public health.

Doctors check liver enzymes before and during treatment because these drugs can damage the liver. If you’re already on other medications, especially for HIV or seizures, your provider will adjust the regimen to avoid dangerous interactions.

How Is Active TB Treated?

Active TB is a medical emergency. Left untreated, it can kill. But with the right drugs, it’s almost always curable. The first two months of treatment use four antibiotics together: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. This combination attacks the bacteria in different ways to stop resistance from developing.

After those two months, you drop pyrazinamide and ethambutol. You continue isoniazid and rifampin for another 4 to 7 months, depending on how severe your case is. That’s a total of 6 to 9 months of treatment. No shortcuts. Skipping doses or stopping early can lead to drug-resistant TB-something far harder and more expensive to treat.

Directly Observed Therapy (DOT) is standard in most countries. A nurse or community health worker watches you swallow each pill. This isn’t about control-it’s about success. Studies show DOT cuts treatment failure and drug resistance by half. If you’re struggling with homelessness, addiction, or mental health issues, DOT gives you the support you need to finish treatment.

Side effects are common but manageable. Rifampin turns your urine, sweat, and tears orange. It’s harmless but startling if you don’t expect it. Isoniazid can cause nerve damage (peripheral neuropathy), so doctors often prescribe vitamin B6 alongside it. Liver problems are the biggest concern. If you notice yellow skin, dark urine, or belly pain, call your doctor right away.

Why Drug Resistance Is a Growing Threat

Not all TB is the same. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) doesn’t respond to the two most powerful first-line drugs: isoniazid and rifampin. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) resists even more drugs. These strains emerge when people don’t take their pills correctly-missed doses, interrupted supply chains, or stopping treatment early.

MDR-TB treatment takes 9 to 18 months. It uses second-line drugs that are more toxic, more expensive, and less effective. Some regimens require daily injections for months. Recovery rates drop to 60% or lower in some regions. In the U.S., MDR-TB is rare but growing. In parts of Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, it’s a crisis.

That’s why completing your full course matters-not just for you, but for everyone around you. Drug-resistant TB spreads just like regular TB. One untreated case can start an outbreak.

Who Should Be Tested for Latent TB?

You don’t need to be tested if you’re healthy and have never been exposed. But if you fall into one of these groups, screening is critical:

- People born in or who lived in countries with high TB rates (India, Philippines, Nigeria, Mexico, Vietnam, etc.)

- People who’ve been in close contact with someone with active TB

- Healthcare workers in high-risk settings

- People living with HIV

- People on immunosuppressive therapy (like TNF inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis)

- Residents or staff of correctional facilities, homeless shelters, or nursing homes

Testing is simple. A skin test (TST) or blood test (IGRA) can detect infection. If positive, your doctor will check your chest X-ray and ask about symptoms. If everything looks normal, you have latent TB-and you can prevent active disease with treatment.

Can You Get TB Again After Treatment?

Yes. Even after successfully treating active TB, you’re not immune. You can be reinfected with a new strain of the bacteria. That’s why ongoing vigilance matters. If you’re at high risk-say, you’re still living in a crowded environment or working in a hospital-you should report new symptoms immediately.

There’s also no perfect vaccine. The BCG vaccine is used in some countries but doesn’t reliably prevent adult pulmonary TB. Research is underway for new vaccines, but none are ready yet. Prevention still comes down to early detection and treatment of latent infection.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat TB?

Latent TB? You might never know it turned active. Or you might wake up one day with a cough that won’t go away, a fever that won’t break, and lungs full of damage. Active TB? Left untreated, it can destroy your lungs, spread to your brain or spine, and cause death. Even if you survive, you might need surgery to remove damaged tissue or live with permanent lung scarring.

And you’ll keep spreading it. One person with untreated active TB can infect 10 to 15 people in a year. That’s why public health departments track cases and offer free testing and treatment. TB doesn’t care about your income, your passport, or your insurance. It only cares if you’re exposed-and whether you get treated.

There’s no shame in having latent TB. It’s not a moral failure. It’s a biological accident. Millions have it. The only thing that matters now is what you do next.

Can you spread latent TB to others?

No. People with latent TB infection cannot spread the bacteria to others. The bacteria are dormant and contained by the immune system. Only those with active pulmonary TB can spread the disease through airborne droplets when they cough, sneeze, or speak.

How long does TB treatment take?

For latent TB, treatment lasts 3 to 9 months depending on the regimen. For active TB, it takes at least 6 months-often 7 to 9 months. Shorter regimens exist for latent TB (like 3 months of isoniazid and rifapentine), but active TB requires a full course of multiple drugs to prevent drug resistance.

Is TB curable?

Yes, both latent and active TB are curable with proper treatment. Latent TB treatment prevents future disease. Active TB treatment kills the bacteria and stops transmission. The key is completing the full course of medication. Stopping early can lead to drug-resistant TB, which is harder and more dangerous to treat.

Can TB come back after treatment?

Yes. Even after successful treatment, you can be reinfected with a new strain of TB bacteria. There’s no lifelong immunity. People at high risk-like those with HIV or working in healthcare-should watch for symptoms and get tested again if exposed.

Do you need a chest X-ray for latent TB?

Yes. A chest X-ray is required to rule out active TB before starting latent TB treatment. Even if you have no symptoms, the X-ray checks for signs of lung damage or active infection. If the X-ray is abnormal, you’ll need sputum tests to confirm whether it’s active disease.

Are TB drugs safe?

Most people tolerate TB drugs well, but side effects happen. Liver damage is the most serious risk, especially with isoniazid and rifampin. Signs include yellow skin, dark urine, nausea, or belly pain. Doctors monitor liver enzymes during treatment. Vitamin B6 helps prevent nerve side effects from isoniazid. Always report unusual symptoms to your provider.

What’s Next?

If you’ve been told you have latent TB, don’t delay. Talk to your doctor about the best treatment option for you. If you’re coughing for more than three weeks, get tested now. TB doesn’t wait. But with the right care, it doesn’t stand a chance.

no one talks about how it just creeps in like a bad roommate who never pays rent

you feel fine until one day you're coughing up a lung and wondering why you didn't listen to that one nurse in 2018