When a new brand-name drug hits the market, it’s protected by a patent that gives the manufacturer exclusive rights to sell it-usually for 20 years. But here’s the catch: by the time the drug is approved by the FDA, years have already passed since the patent was first filed. That means the real window for exclusive sales is often just 7 to 12 years. And yet, many of these drugs stay without generic competition for over a decade. Why? Because patent litigation has become a tool to delay, not protect.

How the System Was Supposed to Work

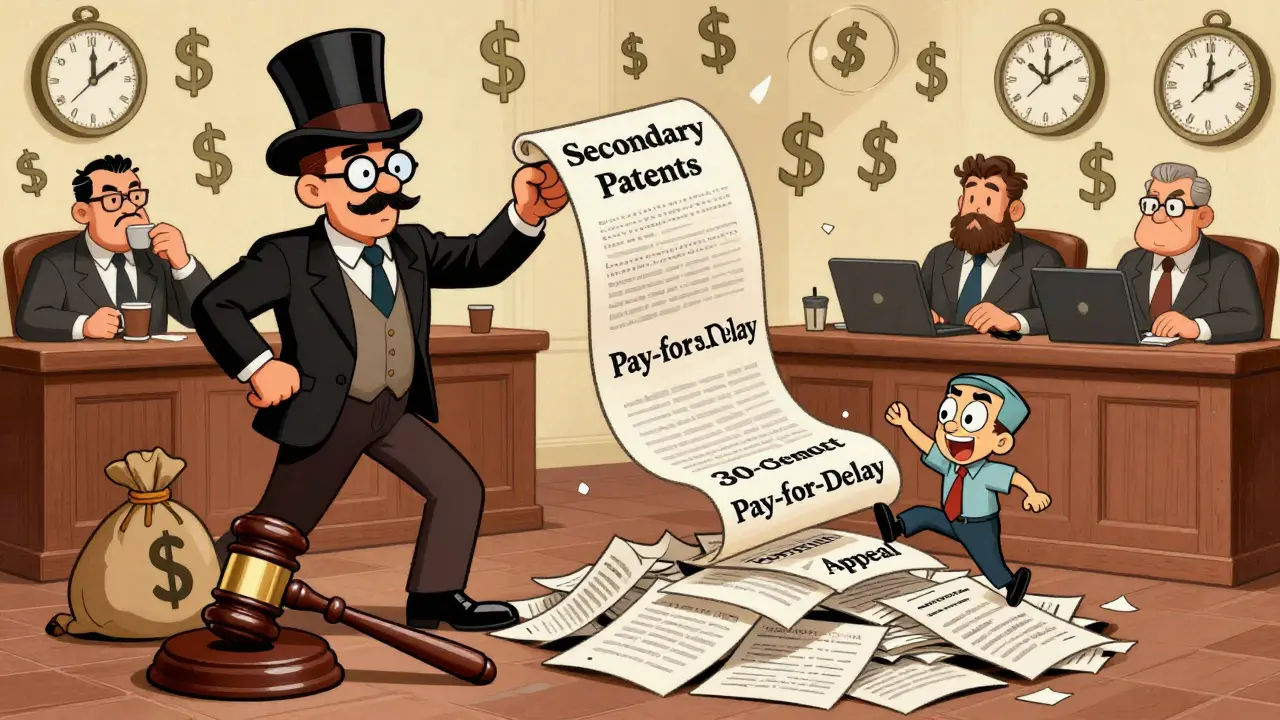

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was meant to strike a balance. It gave brand-name drug companies extra patent time to make up for the years spent in FDA approval. In return, it created a fast-track path for generic manufacturers to bring cheaper versions to market. The key was the Paragraph IV certification. If a generic company believed a patent was invalid or wouldn’t be infringed, they could file a challenge-and trigger a legal clock. Once that challenge is filed, the brand-name company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA is legally blocked from approving the generic for 30 months. That’s not a trial. That’s not a ruling. That’s just a pause button. And it’s automatic. Even if the patent is weak, the clock keeps ticking.What Happens After the 30-Month Clock Runs Out

You’d think that once the 30-month stay expires, the generic would launch. But that’s not what happens. Data from a 2021 NIH study shows that, on average, it takes another 3.2 years after the stay ends before the generic actually hits shelves. That’s more than five years after the patent was challenged. And in some cases, it’s over seven years after the brand drug was first approved. Why the delay? Because lawsuits don’t end after 30 months. They keep going. Brand-name companies file new patents-sometimes dozens-on minor changes like pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods. These are called “secondary patents.” In fact, 72% of patents used in litigation were filed after the FDA approved the original drug. That’s not innovation. That’s legal maneuvering.The Pay-for-Delay Trap

Sometimes, instead of fighting in court, the brand-name company and the generic maker cut a deal. The brand pays the generic to stay off the market. This is called a “pay-for-delay” agreement. It’s not just unethical-it’s illegal under antitrust law. The FTC has been chasing these deals for years. In 2010, they found that even though only 24% of cases involved payments, these agreements cost consumers billions. In 2023 alone, the FTC challenged more than 100 patents tied to big pharma companies like AbbVie and GlaxoSmithKline. And yet, these deals still happen. Why? Because the financial stakes are enormous. The top 10 brand-name drugs facing generic competition brought in $85 billion in annual sales. Delaying a generic by one year can mean an extra $1 billion in profits for the brand.

Who Pays the Price

Patients pay the most. One patient in Chicago couldn’t afford her $1,200-a-month insulin because the generic was approved but blocked by litigation for 18 months. Another Reddit user shared that their friend rationed pills because they couldn’t afford the brand. These aren’t rare stories. They’re routine. Employers pay too. In 2023, delayed generic entry for Humira cost large employers an extra $1.2 billion in healthcare spending. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) now build 24- to 36-month delay windows into their forecasts. They know the system is broken, so they plan for it. Even generic manufacturers lose. Teva’s 2023 annual report admitted that prolonged litigation delayed key products and cost them $850 million in projected revenue. They’re stuck between a rock and a hard place: fight and risk millions in legal fees, or wait and lose market share.The Legal Cost of Waiting

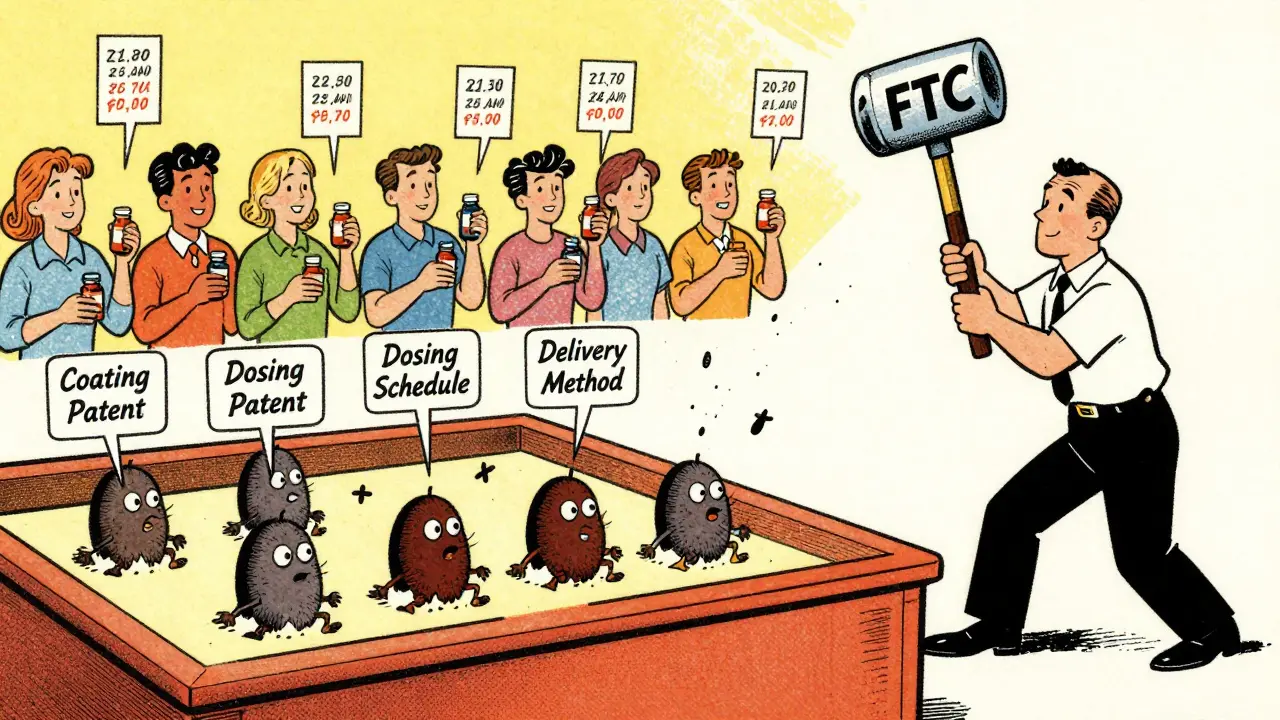

Defending a patent case through trial costs $3 million to $5 million. An appeal? Over $10 million. Most small generic companies can’t afford that. Only the biggest players-like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz-have legal teams of 50+ patent attorneys dedicated to Hatch-Waxman battles. That’s why the top five generic makers now control 45% of the market. It’s not because they’re better. It’s because they can outlast everyone else. And even when generics win in court, the damage is done. The FTC found that generic companies win 73% of cases that go to trial. But winning doesn’t mean launching. It just means they can try again. Brand-name companies keep filing new patents, restarting the clock. It’s a game of whack-a-mole with the law.

So let me get this straight: the system was designed to get cheap meds to people faster, but now it’s just a legal loophole factory? Companies file patents on freaking pill coatings and call it innovation. I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed.

And the worst part? Patients are the ones paying the price-literally. My cousin had to choose between insulin and rent last year. This isn’t healthcare. It’s extortion with a lab coat.

Big Pharma: ‘We need patents to innovate!’

Also Big Pharma: *files 47 patents on the color of the pill*

😂😂😂

I’ve been on a few of these drugs. The generics always work fine. I don’t get why we’re letting lawyers delay them for years. It’s not like the science changed. The pill is the same. The price just went up.

It’s frustrating, but honestly? I’m used to it by now.

THIS IS A GLOBAL CONSPIRACY. The FDA, Big Pharma, and the FTC are all in cahoots. They don’t want you to know that the real cure for diabetes is already in a patent vault in Switzerland. They’re keeping it locked so you keep buying $180,000 insulin. The government is selling your health to Wall Street. Wake up.

They even put microchips in the pills to track your blood sugar. Don’t believe me? Look up Project Monarch. I swear to god I read it on a blog written by a whistleblower who used to work at Pfizer.

Ugh. I’m so tired of this. I get that companies want to make money, but at what cost?

My mom’s on a drug that got generic approval in 2020. Still not available in 2024. She’s on a payment plan. She cries every time she opens the prescription bottle. This isn’t capitalism. This is cruelty dressed up as business.

And yet… we keep voting for the same people who let this happen. We’re all complicit.

Let’s be clear: the Hatch-Waxman Act was a brilliant compromise-until it was weaponized. The 30-month stay? It was never meant to be a permanent injunction. It was supposed to be a temporary pause while courts reviewed the validity of the patent. But now? It’s a delay tactic with a rubber stamp.

And the secondary patents? That’s not innovation-that’s legal gymnastics. One company filed 127 patents on Humira alone. One. Drug. Twelve. Seven.

Meanwhile, small generic manufacturers? They don’t have $5 million to burn on litigation. So they fold. And the market consolidates. Five companies control 45% of the generics market. That’s not competition. That’s a cartel with a law degree.

The CREATES Act? A band-aid. The Protecting Consumer Access Act? Stalled because pharma lobbyists spent $200 million on lobbying last year. And we wonder why prices are rising?

Patients aren’t just paying more-they’re dying waiting. One study showed that every year of delay in generic entry leads to 2,300 excess deaths in the U.S. from untreated chronic conditions. That’s not a statistic. That’s a massacre.

And biosimilars? Even worse. The patent thickets are like mazes designed by someone who hates humanity. We need structural reform-not more studies, not more reports. We need Congress to stop taking pharma’s money and start listening to patients.

And if you think this doesn’t affect you? Think again. One day, you or someone you love will need a drug that’s being held hostage by a patent on a pill coating.

I don’t know why people are surprised. This is America. Everything is for sale. Even your health. Even your life. Even your ability to breathe without paying $10,000 for a pill that was invented 30 years ago.

And the worst part? Nobody gets punished. Nobody goes to jail. The CEOs just get richer. And we sit here arguing about it on Reddit like it’s a debate club. We’re not fixing this. We’re just screaming into the void.

Also, why is no one talking about how the FDA is complicit? They approve the generics. But they don’t enforce the launch. They just sit there. Like a bystander watching a robbery. They’re part of the problem.

And don’t even get me started on PBMs. They’re the real villains. They get kickbacks from the brand-name companies to delay generics. It’s not even hidden. It’s in their contracts. They’re literally paid to keep you sick.

And yet, we still use CVS and Walgreens like they’re our friends. We’re all so naive. So dumb. So trusting. And we wonder why everything sucks.

This is one of those issues where the solution is obvious but the politics are impossible. We need to cap the number of patents per drug. We need to ban pay-for-delay. We need to shorten the 30-month stay to 6 months unless there’s real evidence of infringement.

And we need to stop pretending that ‘innovation’ means filing a patent on a different color of the pill. That’s not innovation. That’s fraud.

The system is broken. But it’s not beyond repair. We just need the will to fix it. And right now, the will is being bought by lobbyists.

You people are naive. You think this is about drugs? No. It’s about control. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t just want to sell you medicine-they want to own your health. Every time you take a pill, you’re submitting to their system. They don’t want you healthy. They want you dependent.

And the FDA? They’re not regulators. They’re gatekeepers. They’re paid to say yes. The patents? They’re just tools to keep you in line.

Look at the numbers. The average person takes 4.5 prescription drugs. That’s not coincidence. That’s design.

And you’re all sitting here talking about lawsuits and patents like it’s a game. It’s not. It’s a war. And you’re the battlefield.

the system is rigged. always has been. big pharma owns congress. they own the fda. they own the courts. they own the media. they own your doctor. you think you have a choice? you think you’re free? you’re a customer. a product. a number on a balance sheet. they dont care if you die. they care if your insurance pays. and if you cant pay? you dont deserve to live. thats the truth. no one wants to say it. but its true. i saw my brother die because he couldnt afford his med. they told him to wait. for 2 years. he waited. he died. and they made more money. they always do.

I just want to say thank you to everyone who’s been fighting this. The activists, the small generic makers, the whistleblowers. You’re not heard enough.

And to the people who think this doesn’t matter: it does. I’ve seen it. My dad had to choose between his heart medication and groceries. He chose groceries. He died three months later.

We need to stop treating healthcare like a commodity. It’s a human right. And if we don’t fix this, we’re not just failing patients-we’re failing ourselves.

Let’s cut the crap. The solution is simple: ban secondary patents on non-functional changes. Limit the 30-month stay to 6 months. Criminalize pay-for-delay. And fund public generic manufacturing.

It’s not complicated. It’s just inconvenient for the people who profit from this mess.

Do it.

Actually, I just read something that made me furious. The FTC found that 87% of the patents used in these delays were filed after FDA approval. That means they weren’t protecting innovation-they were protecting profits. And the worst part? The courts keep letting them get away with it.

There’s a case right now where a company filed 14 patents on the same drug over 8 years. Each one triggered a new 30-month stay. The generic company finally won in court after 11 years. The drug was already obsolete by then. No one needed it anymore.

That’s not justice. That’s a death sentence with a law degree.